Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Watermen

Generations of independent fishermen have found a home on the waters of the Chesapeake Bay. Called watermen regionally, they share a love of the estuary and of making a living by harvesting blue crabs, finfish, and oysters.

Watermen toil alone or in small groups. Their commitment to one of America’s most treasured natural resources earns them a measure of respect throughout the Chesapeake region.

Learn more on Maryland Sea Grant's YouTube channel by watching videos under the Chesapeake Bay Watermen playlist.

See these Maryland Sea Grant publications about the lives of watermen:

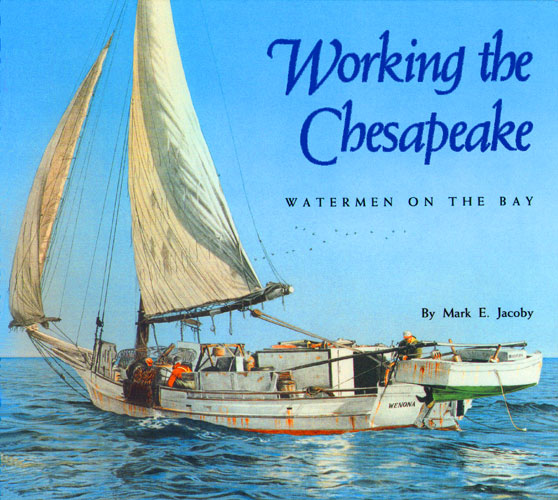

- For a broad overview of the life and work of Chesapeake Bay watermen, check out the Maryland Sea Grant-published book Working the Chesapeake: Watermen on the Bay. Author Mark Jacoby spent time aboard ships with watermen who harvest Bay species in a variety of ways through all four seasons, hearing firsthand about their lives spent on the water. Jacoby’s work gives us the people and places that define the region’s special character, presenting their own views on what may be a disappearing world.

- African Americans have been harvesting and sailing the Bay since first coming to its shores, but stories particular to their lives are not as well known. To chronicle this aspect of Bay culture, Maryland Sea Grant produced two newsletters — one about three independent watermen who harvested oysters from their own boats, and another about men who hauled menhaden into huge nets for commercial ships while singing chanteys. You can read those stories here: Black Men, Blue Waters and Menhaden Chanteys: An African American Maritime Legacy.

- Watermen are often characterized by their resilience in the face of many challenges to their way of life, both societal and environmental. In his book Heritage Matters: Heritage, Culture, History, and Chesapeake Bay, (a part of the Chesapeake Perspectives series), anthropologist Erve Chambers of the University of Maryland, College Park, describes how watermen pass down skills and daily lessons of life, creating a “cultural heritage.” Chambers argues against the popular notion that Bay cultures are dying. He expresses faith in the abilities of local communities to adapt and change.

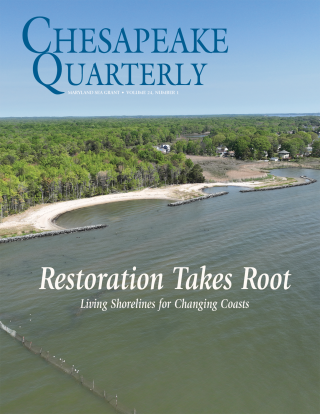

- Another anthropologist at the University of Maryland, College Park, Michael Paolisso spent years getting to know watermen and their culture. He also conducted a series of meetings that brought together watermen, scientists, and managers to discuss their differing opinions about Chesapeake Bay. Read about the results of his work in, Following Those Who Follow the Water, an issue of Chesapeake Quarterly, Maryland Sea Grant’s magazine. And in this video: