Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

The Jellywalk: Assessing Jellyfish Abundance and Diversity along the CBL Pier

It was a typical summer afternoon back in June 2015 on Solomons Island, home to the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory. I was sitting on the front porch of my office building, reading a book about menhaden, when I looked up. I noticed Ph.D. student Suzan Shahrestani jaunting across the yard towards our pier. When I asked what she doing, she said she was about to conduct her “jellywalk.”

“What’s a jellywalk?” I asked.

“I’ll show you,” she replied, gesturing towards the pier. “Why don’t you come with me?”

Intrigued, I dog eared the book and followed. We walked onto the dock, across the street, entering in the access code, hastening though the metal gate adorned with plaques touting the achievements and ongoing projects occurring here. Then we sauntered along the dock’s edge, “peering” (if you’ll allow the terrible pun) into the waters, trying to spot any jellyfish. As we advanced, Suzan explained her task.

Several times a week, usually in the morning, she walks the perimeter and counts Atlantic sea nettles (Chrysaora quinquecirrha), a common species of jellyfish in the Chesapeake Bay. Against the clear waters of the bay, they usually stand out at the surface, like a softly undulating piece of white plastic about the size of your fist.

This walk has been conducted off and on by a succession of investigators for more than 50 years, began in 1960 as the brainchild of David Cargo, a scientist at Chesapeake Biological Laboratory (CBL). Five days a week, Cargo recorded the number of jellies he observed off this exact pier. When he retired in 1990, Cargo entrusted the task to younger scientists including current Smithsonian Environmental Research Center scientists Rebecca Burrell and Denise Breitburg who revitalized and publicized the project in the mid 00’s. With each generation, the complexity and uniformity of the study increases. Contemporary observers now record data on water clarity, cloud cover, and the calm/choppiness of the water.

|

|

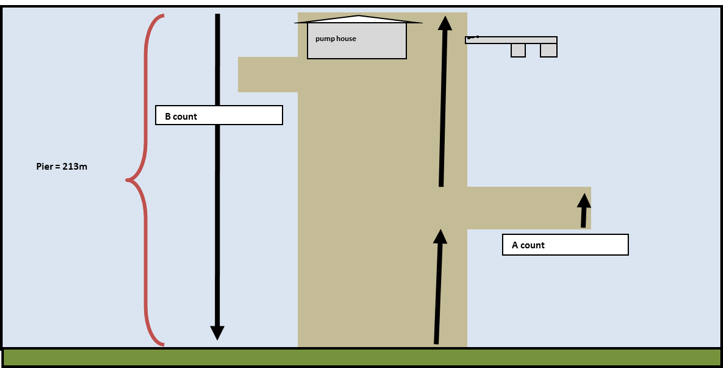

Diagram of the prescribed jellywalk technique. The observer must follow the arrows indicated. Credit: S. Shahrestani |

Today, this is the responsibility of Suzan, a graduate student under Dr. Hongsheng Bi. A third-year Ph.D. student, Suzan has been doing the jellywalk since 2013, so she has personally experienced the seasonal and yearly trends. Typically in the winter there are no sea nettles. In fact, in many years the jellywalks were suspended between late fall and early June. But during summer, when conditions for jellyfish are favorable, the pier might be surrounded by dozens or hundreds of jellyfish within sighting range.

Though great news for jellyfish lovers, this is terrible news for most everyone else. Large gelatinous clumps of jellyfish have clogged intake pipes and disrupted normal functioning at nuclear power plants, including the Calvert Cliffs plant on the Chesapeake Bay. The adjacent Calvert Cliffs State Park, a popular tourist beach, has had to warn their visitors about the jellyfish, advising their swimmers to be aware of this nuisance.

And if you thought there would be a simple solution to controlling their numbers, think again. Physiologically, jellyfish are practically immortal. They can consume ten times their weight every day, they can out-eat, out-grow, and out-survive their competitors, and can exponentially reproduce by cloning -- no burdensome mating rituals for them. Though they might be one of the most hypnotic displays at the aquarium, jellyfish are potentially ticking time-bombs of environmental chaos. Given the right ecological conditions- conditions like warm waters and higher currents -- jellyfish may be able to dominate an animal community, damaging ecosystem and economy alike. However, the details of this relationship are an ongoing topic of research.

Scientists at CBL are using the extensive jellywalk data to better predict jellyfish population explosions in the Bay. We can identify the years with higher-than-average abundance and look to varying environmental conditions like water temperature, salinity, and upstream river flow as possible culprits to explain the surge -- jellyfish are especially tolerant of high temperature and salinity.

I wanted to do my part to piece together the puzzle, even though the furthest I ever stray from my computer is to the electric kettle. I’m a modeler, someone who designs computer programs that can simulate environmental conditions or processes, such as population growth. With a group of students including Suzan and Sea Grant Fellow Hillary Glandon, I built one such simple model of changes in jellyfish abundance over time.

|

|

David Cargo, a scientist who began the jellywalks along the CBL pier in 1960, examines a preserved jellyfish. Credit: Chesapeake Biological Laboratory Library |

We presented this work at the American Fishery Society’s Tidewater Chapter meeting in April 2016 in a poster titled “Gettin’ jelly with it: The influence of local environmental conditions on gelatinous zooplankton abundance observed at the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory Research Pier and the potential interactions with fish abundance and diversity.”

We found that higher temperature in the spring before a jellyfish bloom was the best predictor of peak abundance. You would think that a jellyfish bloom might have a negative effect on the population of other species -- that more jellyfish would mean more consumption of resources, leaving less for the Atlantic silversides or Bay anchovies. But actually we found the opposite to be true! We think that similar environmental factors (warmth, increased nutrients, etc.) are influencing all the animal species, fish and jellyfish alike. We will continue to monitor both fish diversity and jellyfish abundance with these long-term data sets and look forward to seeing how these trends continue into the uncertain future.

But back on that June day when I first tagged along with Suzan on the pier, this future project was far from our minds. We were just content to collect the necessary data and enjoy the sunshine. Not that there was ultimately any data to collect that day. Climate conditions last year brought a cool spring, and as a result we saw few jellyfish. But I was happy for the chance to learn a little more about one of the ecology projects happening around me. If I always kept my nose buried in a book or on my computer screen, I’d be sure to miss them!

Photo, top left: Jellyfish observed off of the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory pier. Credit: Matthew Damiano

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog