Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

A Photographer Eyes the Bay

The man who taught me the most about photography never told me anything about cameras or lenses or film types. His name was Robert de Gast, and years ago he showed me how to see the Chesapeake Bay through a camera lens.

De Gast died last year, but his work lives on through his five books about the Chesapeake and through his influence on current Bay photographers. You can see some of his work in a recent issue of our magazine, Chesapeake Quarterly (Volume 15, #4). And for the next year, you can see much more of his work at an exhibition of his Bay photographs that recently opened at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michael's, Maryland.

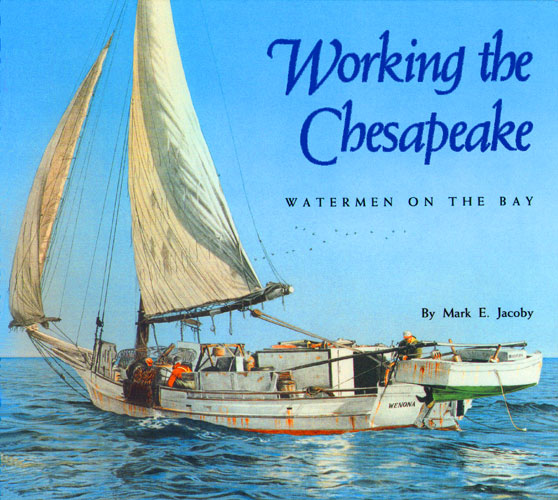

I first went looking for de Gast back in 1978 after I found a copy of his book The Oystermen of the Chesapeake. As the communications leader for a new marine science program, I was determined to feature great photography in our publications. The new program, Maryland Sea Grant, was going to focus its early work on the state's struggling oyster industry, and de Gast's book held some of the most striking images I had seen of the men who fished for oysters in the winter waters of the Chesapeake Bay.

For the cover on the first publication ever produced by Maryland Sea Grant, I wanted to feature this photograph by de Gast:

.jpg)

I loved this image (and still do) because it manages to be so natural and so artful. Its composition is striking in its formal, symmetrical design. In a scene busy with sailing boats, de Gast subtly focuses our attention on a solitary waterman in the stern of one small, motor-driven boat. He captures the waterman at the moment he stands silhouetted in a frame within a frame: He is centered in the space between his mast and its support rigging, and his boat, in turn, is again neatly centered in the space between five large sailing vessels.

There is art in the image--and there is history also: the sailing vessels are skipjacks, fishing craft out of an earlier century that were still using only the wind to drag iron dredges across the oyster bars that grow along the bottom of the Bay. The small boat, however, is not only motor driven; it is also equipped with a mechanized patent tonging rig that uses hydraulic power, rather than wind power, to dig oysters off the bottom and hoist them aboard.

And there's subtle drama in the scene: the solitary tonger approaches an area already crowded with sail-driven dredge boats, each of them carrying a crew of watermen who may not be happy about this motorized, mechanized watermen invading their ancient oystering grounds. In the lone tonger's stance and gaze you can sense a sort of wariness. So there's history, meaning, and emotion in the photograph--but it's de Gast's artful eye that found and shaped the image in a way that could grab and arrest and focus our attention.

Such wonderful Bay photographs, it turned out, were produced by a native of the Netherlands. Raised in The Hague, de Gast was a teenager when he moved with his family to Queens Village, New York, where he went to high school and trade school. To improve his English skills, he moved to Oklahoma to work on a ranch. And to improve his photography skills, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, where the Signal Corps trained him as a photographer. By the time I met him, he had settled in Annapolis, fallen in love with sailing, and established himself as a successful commercial photographer.

.jpg)

Robert de Gast aboard his small sailboat, mapping out his circumnavigation of the Delmarva Peninsula

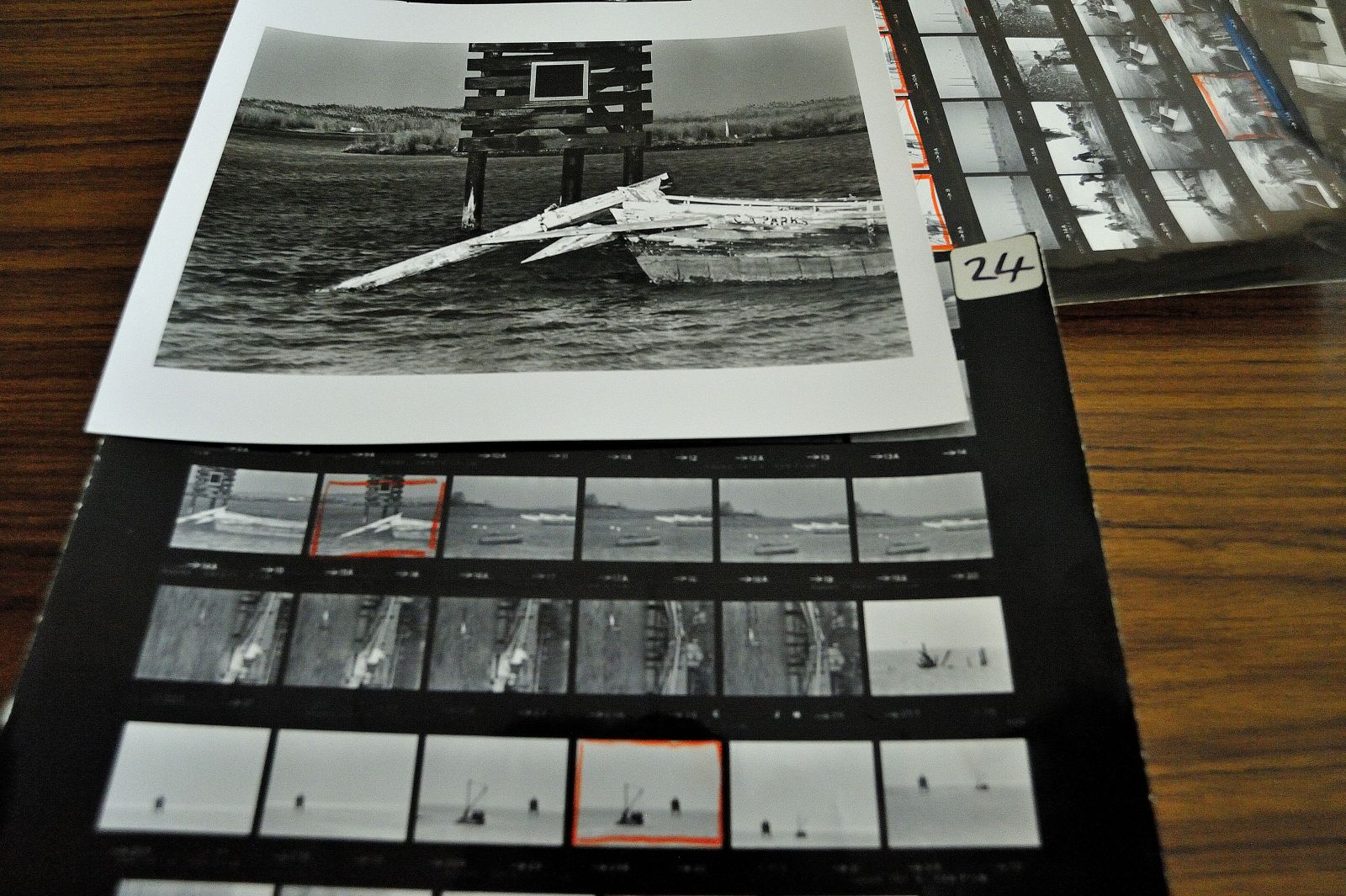

When I reached him by phone, de Gast invited me to his house, and there I found a lean and thoughtful man who would give me an unusual suggestion. He listened quietly while I explained why we wanted to buy some of his photographs and why we couldn't pay very much for them. His book held 165 black-and-white photographs--I had already seen these--but he told me he had many more images that I had not seen. Did I want to look through all those photographs? When I said yes, he told me he had taken 6,000 photographs for this one book.

A contact sheet, one of hundreds, with 30 thumbnails--but only one image chosen for printing

How was I supposed to examine 6,000 photographs? By looking through contact sheets. In the long-ago days of black-and-white film, a photographer like de Gast could not instantly check his images on his digital camera. Instead he had to return home, process his film, lay strips of film onto photographic paper--and print a contact sheet, a collection of thumbnail images. Only then could he finally review his work and begin to pick out his best images.

Two watermen and an oyster dredge framed and silhouetted by a series of diagonals: the boom, the side of the boat, and the slash of early morning sunlight on the water

He would bend over each contact sheet with a loupe, a small 10x magnifying glass, and he would carefully examine each tiny image--much like a jeweler counting carats on a diamond. With a grease pencil he would carefully outline the gems that he liked. These were the negatives worth taking into a darkroom, worth polishing into a print.

At our Annapolis meeting, de Gast handed me two boxes that held all the contact sheets for all the shots he had taken during his time with oystermen. "Take a look through these," he said. "You might find some other shots that might work for you." I carried the boxes home, wondering whether it was worth my time to wade through them.

It was. I found myself going to school on his contact sheets. Poring over them became, for me, a graduate course in photography. Different photographers have different strengths, and Robert de Gast, I discovered, was a master of composition, one of those mysterious qualities that lets certain photos stand out, that lifts some to the level of art.

My discovery came in stages. The first stage found me with my eye pressed against a loupe inspecting thumbnails of his photographs. Composition is the art of arranging the elements in an image, creating an order that leads the eye to the true subject of the photo and focuses the mind on the possible meanings of the image.

.jpg)

The mysterious magic of composition: two patent-tonging watermen on their motor-driven boat with the triangle of the rigging creating a frame for one waterman and for the distant triangles of two skipjacks under sail

Great composition is easier to appreciate than to explain--but we always know it when we see it. And I was seeing it as I worked my way through all those contact sheets holding all those images de Gast made of oystermen at work. With his book laid open to a photograph I liked, I could trace on the contact sheet the series of shots that led up to and followed the image he printed. I saw the slight adjustments in framing, the alterations he tried in balance, leading lines, diagonals, depth of field, and point of view. All these tweaks until voila: he had the image he wanted--an order that focused the eye and the mind and showed us something vital about the world of oystermen.

As I pored over his contact sheets, an education was in process, somewhere behind the eyes, deep in that part of the brain that responds to great images and remembers them and absorbs them. Emerging from my encounters with his contact sheets, I could not explain to anyone or even myself the keys to composition, but I could sense it when I saw it through a lens. I could feel an image click in my head even before I heard a click from my camera.

A contact sheet, a thumbnail image, a composition that worked, a boat that died, an image that lived

A contact sheet, a thumbnail image, a composition that worked, a boat that died, an image that lived"A photograph is not an accident, it is a concept," said Ansel Adams, the great nature photographer. And de Gast was teaching the same lesson. See the photograph in your mind before you make the photograph with your camera. Learn the patience to find and wait for the scene to take shape, focus on the background as much as the foreground, pay attention to the power of negative space, bring the tools and the training and the technique to capture the scene. And bring the readiness to respond when the right moment arrives.

De Gast taught other lessons also. Great composition, I discovered, does more than show us how an artist sees: it also expresses how he thinks and feels about the piece of the world he's captured with his camera.

That's how memorable photographs educate us. There is a part of the mind that holds extraordinary images in memory and discards the mediocre and the mundane as ephemeral clutter. Think of a poem or a piece of music you hold in your memory, then think of listening to it again:

Before you call him a man?" --Bob Dylan, "Blowin' in the Wind"

.jpg)

Once again, a collection of triangles and a frame within a frame: a waterman's head centered in the middle of his tonging rig and his rig centered between sailing skipjacks

How did he catch such perfect formal framing? Especially when he's shooting a moving boat while standing on another moving boat? Whenever he went out on skipjacks and tonging boats or marine police boats, de Gast worked with four cameras strapped to his body, an approach that let him work quickly. When the idea took shape in his head, when the scene took shape in front of him, he would be ready to pounce, waiting for what another photographer called "the decisive moment." Out of a passing moment, a lasting image.

Many of Robert de Gast's most memorable and lasting images are now on display at the year-long exhibit that the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum has organized in St. Michael's. To set up this show, curator Pete Lesher gathered and reviewed more than 10,000 photographs that de Gast made about oystermen, lighthouses, sailing trips, and abandoned homesteads along the Eastern Shore.

.JPG) Pete Lesher, curator for the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, with some of the contact sheets and prints that he culled through for the new exhibit

Pete Lesher, curator for the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, with some of the contact sheets and prints that he culled through for the new exhibitLesher also asked David Harp to write the essay that introduces the exhibit catalog. Now one of the Bay's best known photographers, Harp works in color, but was influenced by de Gast's black-and-white work back when he was beginning his own career creating images of the people and places and rivers of the Chesapeake region.

Whether de Gast's influence ever turned me into a competent photographer is for others to judge, but all those contact sheet seminars educated a decent photo editor, one who had at least learned how to recognize a good photograph. The evidence for that education can be found in the annals of the magazines that Maryland Sea Grant has published over the years, both in print and online. There you'll also find images by photographers Aubrey Bodine, Marion Warren, David Harp, Jay Fleming, Skip Brown, and Nick Caloyianis.

If I also learned from each of these artists--and I think I did--it was primarily because Robert de Gast managed years earlier to open my mind and my eye. He was my first mentor, the one who taught me the most about photography, about art, about how to look through a lens at the worlds of Chesapeake Bay.

Books about the Chesapeake region by Robert de Gast:

The Oystermen of the Chesapeake (1970), The Lighthouses of the Chesapeake (1973), Western Wind, Eastern Shore: A Sailing Cruise around the Eastern Shore of Maryland, Delaware and Virginia (1975), Unreal Estate: The Eastern Shore (1993), and Five Fair Rivers: Sailing the James, York, Rappahanock, Potomac and Patuxent (1995)

Photographs are property of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. Photographic scans provided by Richard Anderson Productions, Baltimore, MD

See all posts from the On the Bay blog

.JPG)