Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

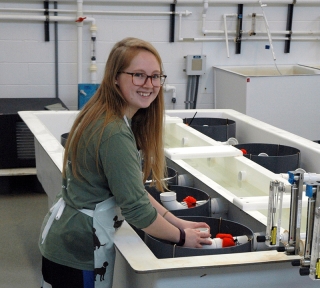

All Things Oyster: Whether studying their genomes or helping farmers grow them, Brittany Wolfe is building a career on oysters

Most kids spend their time at the beach swimming and playing in the ocean. Not Brittany Wolfe. Growing up surrounded by water on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, she was more interested in poking around the intertidal zone, finding shells and wondering about the animals that lived in them.

When the local community’s shellfish management division began reseeding oysters to filter the water in an area that had been closed to fishing, she jumped in to help. But her interest in shellfish really took off as a marine biology student at the University of Maine (UMaine), where she worked all four undergraduate years at the school’s Aquaculture Research Center and focused her senior project on Roseovarius Oyster Disease (ROD), which affects the bivalves in Maine waters.

Now, as a Maryland Sea Grant Extension specialist and the shellfish hatchery manager at Morgan State University’s Patuxent Environmental & Aquatic Research Laboratory (PEARL), Wolfe is working across the breadth of oyster aquaculture, from supporting research in shellfish genomics in the lab to helping provide information and resources to oyster growers in the field.

The majority of her time is spent supporting the work of PEARL’s shellfish scientist Ming Liu and the Oyster Genomics Breeding Program. “I’m in charge of the hatchery first, just continuing the breeding program and offering support to other researchers who need to use the space and support Ming Liu’s research,” she says.

The Extension portion of her job is to support members of Maryland’s aquaculture industry. “They kind of go hand-in-hand,” she says. “I can go out to the farms to troubleshoot problems and provide knowledge and a link between the research world and the industry.”

Wolfe honed her knowledge and expertise in aquaculture when, after taking a little time off after graduating from UMaine in 2012, she earned an internship at the Oyster Aquaculture Training program at the Aquaculture Genetics and Breeding Technology Center, which is housed at Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS).

“They train interns in every aspect of oyster aquaculture in hopes of putting them in jobs in the industry,” Wolfe says. After her six-month internship in 2014, she worked in the industry for a short stint before returning to VIMS, first to cover for the algologist who went on maternity leave, then landing a permanent position as the polyploid specialist in charge of all the triploid and tetraploid oysters in the field as well as spawning them in the center’s hatchery.

In 2017 she headed to the University of North Carolina Wilmington (UNCW) to get her master’s degree in marine biology. There, she researched how tetraploid oysters lose chromosomes over time, a process called reversion.

“As they lose chromosomes their DNA shows up more as triploid oysters,” she says. “They have a combination of tetraploid and triploid DNA.”

Under the advising of Ami Wilbur, director of UNCW’s Shellfish Research Hatchery, Wolfe is completing her master’s this summer, after two hurricanes interrupted her research. “Hurricane Florence killed a good portion of my oysters, which was unfortunate. Then the next year Dorian hit and we shut down for that too.”

Now, with COVID-19 restrictions an issue, she says PEARL has received special permission to continue its spring spawning with limited staff and social distancing protocols. The disruption from the pandemic has given her more time to focus on the Extension side of her position, which is conducive to working from home. She’s been getting to know members of the industry and learning what their needs are and how she can help, including keeping them up to date on funding sources such as the Pandemic Adjustment Loan Fund (PALF) and Pandemic Adjustment Equipment Grant Fund (PAEGF).

“So much is related to COVID-19 and relief for the industry members,” she says. “There’s so much information out there, so I’m trying to be on top of all of it to be able to pass that information on to the industry members so they know what’s going on.”

When she’s not spending time in and around oysters and aquaculture, she’s playing with her dogs, gardening, and dabbling in visual art across media—from colored pencil to stained glass and ceramics—focusing on pieces related to marine biology and subjects in nature.

“I’ve painted a bunch of pictures of oysters,” she says. “My goal is to be able to have paintings for my house that are marine biology themes.”

Read more on triploid oysters from the Chesapeake Quarterly archive:

Trials & Errors & Triploids: Odyssey of an Oyster Inventor

See all posts from the On the Bay blog