Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

My Pursuit to Understand Society through Science (and Vice-Versa)

Sometimes I feel like great scientific insights are not having an impact in societal and governmental decisions. That is particularly the case for climate science, but it is also in different scientific fields (e.g., engineering, forensic science, smart cities, etc.). As researchers, we like to think we know better, and that if others would know what we know the world would be a better place. It turns out the world does not run on facts only. It is sustained by social relationships and cultural values.

My time as a graduate student has now led me to believe that relationships and communicating what we do to others with respect and empathy is more important than stand-alone scientific findings. Creating and evaluating new spaces where people from different backgrounds in a given community can come together has been shown to lead to collaborative learning, where perceptions of an issue can be addressed with collaborative problem-solving and decision-making.

It is my view that researchers are generally not trained to engage and communicate with the broader public and decision-makers in these types of collaborative settings. Graduate students could benefit from having courses and experiences in participatory research, where scientists, from diverse disciplines, and non-scientists collaboratively learn about a problem and explore research directions and solutions where science can best serve the needs of the people.

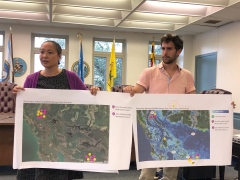

Scientists can learn much from the residents of a community about any given research subject. Likewise, citizens, local leaders, and policymakers can learn from scientists how a certain issue is being studied. Such an effort was successful recently on the Eastern Shore as climate scientists, oceanographers, anthropologists, and landscape architects collaborated with government officials and residents of rural communities to provide a clear and science-based picture of what the future looked like and come up with solutions to safeguard it.

|

|

Sea level rise and how to prepare for it is one area in which collaborative learning among scientists, residents and government officials. This house on Deal Island has already succumbed to the coming changes. Photo credit: Rona Kobell |

Science has always played a key role in shaping policy throughout history. I recently heard a lecture by Steve Fetter, dean of the Graduate School at University of Maryland and professor at the School of Public Policy, where he explained how he and other physicists were working with the government during the Cold War to prevent nuclear weapon proliferation. Donald Boesch, president emeritus of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, is another example of a scientist with a successful track record of influencing environmental and conservation policy.

Climate science—and science in general—continues to struggle its way to the mainstream American consciousness, which means more work needs to be done in increasing the engagement between science and the public. The meeting ground between scientists and the public can be understood as a “boundary” – where people who have relationships with both scientists and decision-makers as well as expertise in working in this “boundary” facilitate a process of discussion and consensus-building.

An important factor that determines the learning experience of all participants is respect and empathy. Boundary spanning organizations (like Maryland Sea Grant) or NGOs (like the Eastern Shore Land Conservancy or The Nature Conservancy) play an important role by engaging scientists, government administrators, community leaders, and local government officials to facilitate collaborative learning and design locally-relevant actions that are scientifically-grounded.

It is those spaces and relationships that I research. Currently, the title of my dissertation proposal is: “Studying the ties that bind climate science and practice: A case study of a coastal community in Maryland.” I want to understand the degree to which human relationships contribute to change in perceptions (a.k.a., social influence). I believe this knowledge can take us a little bit closer to understanding the potential of communication, especially from scientists to the public.

In my journey to become a socially-relevant researcher, I have found that the answer to influencing others is through establishing close ties with those we disagree with – ties that are supported by trust and mutual respect. My preliminary findings suggest people in some communities in Maryland share perceptions of climate impacts with those they interact with on a regular basis and whom they perceive to respect them.

In the same way, I have learned a lot about how science and public engagement work. I wish many graduate students experienced that kind of engagement and developed effective skills to engage and communicate with our fellow citizens. It may not be in the curriculum, but it is crucial for future success.

Photo, top left: Victoria Chanse, associate professor and master of landscape architecture program chair at University of Maryland, with graduate student Sebastian Velez-Lopez at a collaborative learning meeting with Smithville residents in Cambridge. Credit: Rona Kobell

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog