Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Things Will Go Wrong, and That’s Okay! Adaptation Is Key

I have had many friends tell me I am calm and collected. They see me as a beacon of relaxation and tranquility who has everything figured out. They could not be more wrong, at least about my academics. In this part of my life, I always try to stay one step ahead with project planning, paper writing, and completing homework. I was confident that I would get through my PhD without missing a beat.

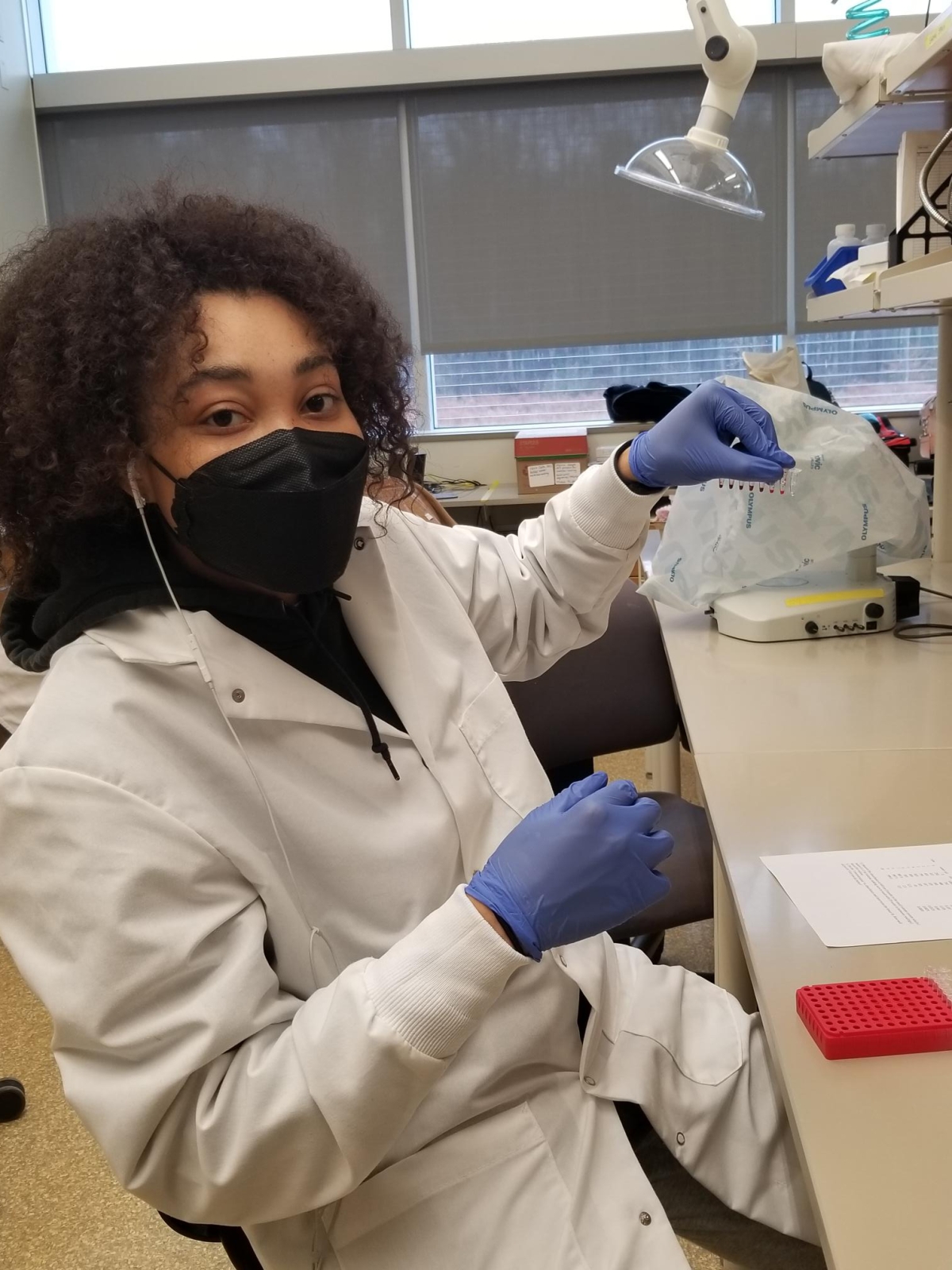

It almost feels laughable that I had that thought at the start of my fellowship journey. Now, I have dealt with squid delivery delays, manuscript edits that took more than a year to finish, and managing three interns at once. There have been nothing but setbacks, altered deadlines, and endless cups of tea to soothe my nerves.

Implementing my own research definitely opened my eyes to the reality that a marine science project cannot be planned to a T ahead of time, especially genetics projects. I have now learned that it is nice to have a plan, but there is no guarantee it will work. Essential equipment can give false readings, mistakes can lead to spoiled samples, and research funds must be readjusted at each stage. Sometimes, every little thing that can go wrong will go wrong. Even things you did not think were possible can go wrong.

For instance, I was using an instrument to amplify DNA in my samples, and nothing was working. I thought I was going to lose my mind because I would go through the procedure at a glacial speed, double checking every step, and still ending up with no results. It was challenging not to take all the mistakes personally because I felt like I was failing as a scientist. No one could figure out what was going on until a research technician in our lab used a different batch of an essential ingredient in the sample DNA amplification. We had been stumped for two weeks, and it turned out to be faulty materials that caused the problem. All that stress, discouragement, and doubt due to a bad batch of enzymes.

Even though it was hard for me to deal with, I am currently learning that nothing will be fixed if I wallow in frustrations. There is not much in life that works perfectly the first time around, so it’s safe to assume that my PhD work will not go perfectly either. It is still incredibly hard to move past these mistakes sometimes, especially when I feel like I am making no progress in my projects. However, I always find new ways to push through. Nowadays, I listen to funny podcasts and bop around to my music in the lab while I wait for results. That way, even though I may not get the result I want, I'm still able to enjoy myself for part of the day. And I consider that a win.

If you can figure out a way to keep going and enjoy what you are doing, then you are going to be okay. Additionally, much of this work cannot be done alone. I know quite a bit of mine sure wasn’t. I was able to get through my “gauntlet semester” by having a wonderful support system of loved ones, friends, and incredible advisors. Each of them reminds me that I am one step closer to achieving my dreams, even when things go wrong. I have learned that I must adapt to the situation and find the solution. I mean, if organisms were able to adapt to survive the numerous stages of Earth’s history, then I’m sure I can find a way to prosper during my PhD.

Top Left Image: Lyana Oliviel and Roberta D'Camp, interns working with Leone Yisrael, pipette DNA samples from Yisrael’s research. Photo: Leone Yisrael

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog