Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Finding the Positive in Rejection

Nearly two and a half years after starting my PhD research at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, I was finally ready to submit my first-author manuscript to a scientific journal.

I arrived at the Horn Point Laboratory in August 2014. I immediately began working on research to understand sediment-vegetation interactions within a large underwater grass bed at the head of the Chesapeake Bay. This grass bed is on the shallow shoals at Susquehanna River’s mouth in an area known as the Susquehanna Flats. During the summer months, the Susquehanna Flats teem with dense vegetation stretching to the water’s surface, providing habitat and protection for numerous juvenile fish, crustaceans, and mollusks. These underwater grasses only recently recovered after disappearing in the 1970s. Although previous work revealed that water quality improvements provided the right environmental conditions for the grass bed to return, the focus of my research was to understand how the presence and absence of this vegetation affected sedimentation.

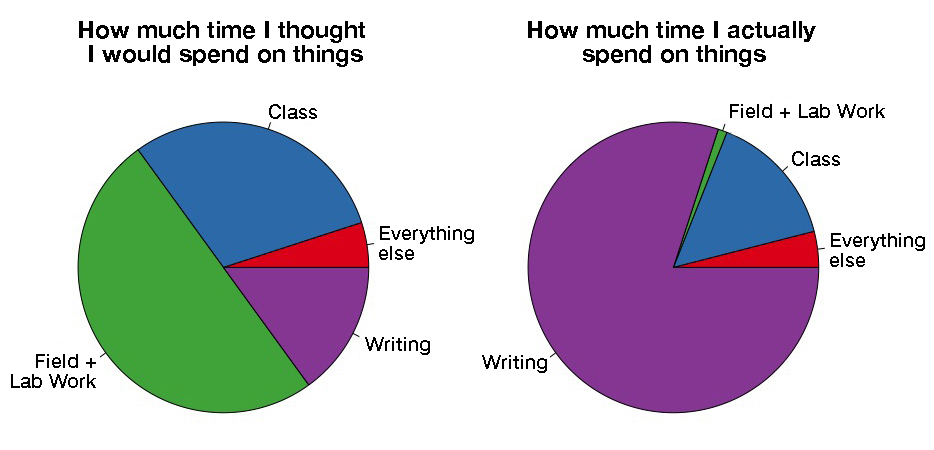

I was able to dive headfirst into the graduate experience by going out to collect sediment on the Susquehanna Flats. I ended up going into the field three times that first year, and spent a hefty portion of my time running analyses in the laboratory. Previous to starting graduate school, I envisioned an environmental scientist as someone who spent most of his or her time in the field or in the lab; however, I have learned that the most time-consuming part of the research process, at least for me, is writing a manuscript.

How I imagined I would spend my time as a graduate student researcher vs. how I really spend my time as a graduate student researcher. Credit: Emily Russ

I created a word document for my manuscript sometime in the spring of 2016. Initially, I experienced writing inertia, along with the insecurity that my writing was not good enough to be published, but was able to overcome it after my advisor told me to relax my standards of trying to write everything perfectly and to just put information on the page. Eventually, I produced a rough draft that began to resemble a scientific paper. Several revisions later, my advisor told me she thought I was ready to submit. I felt confident about this manuscript, and I was more than ready to send it off.

Unfortunately, I received an up-front rejection from the journal saying that they did not feel that the work was an appropriate fit. That was tough to hear, but I realized it meant I needed to choose a journal that would be a better fit for this research. After a little reformatting, I submitted my manuscript again to another journal.

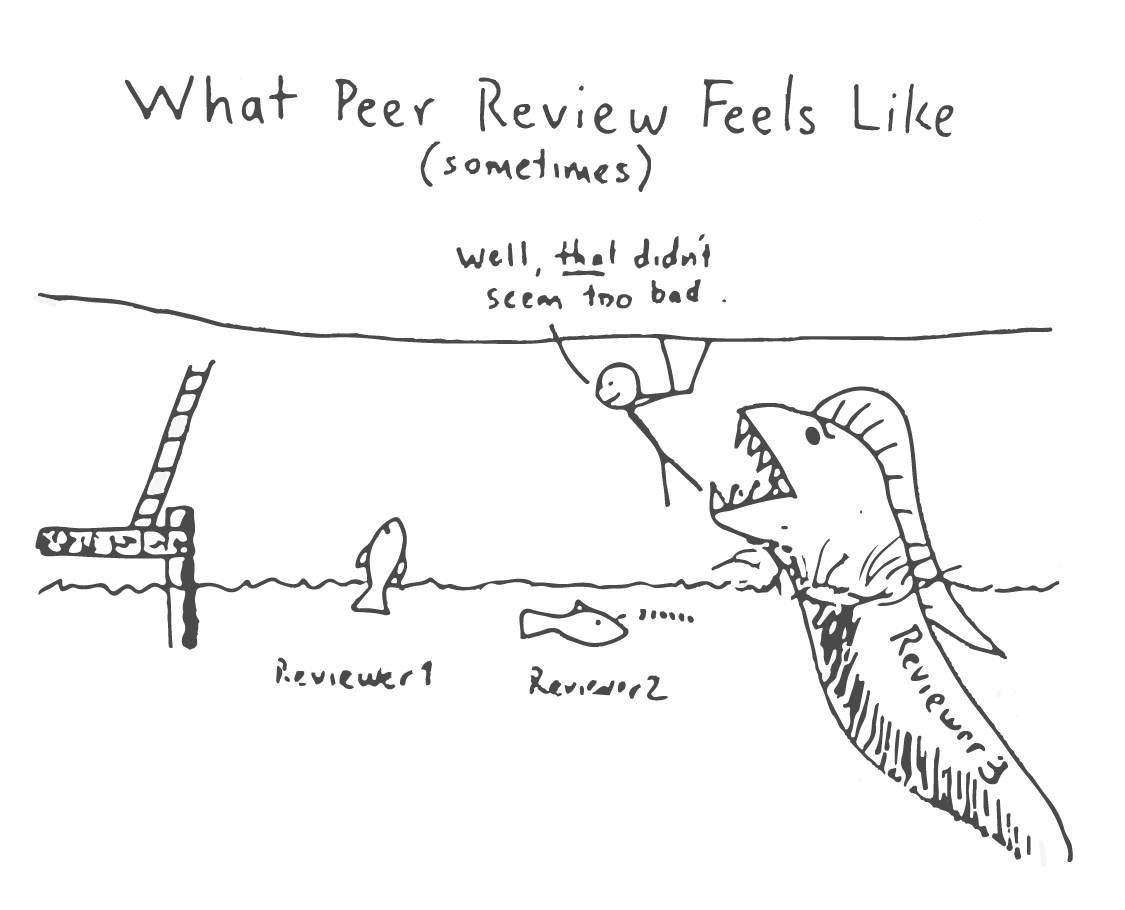

A couple months later, I received another rejection, but this time it was because the reviewers had several major concerns about the work. After my first cursory read of the reviews, I became upset, and took many of the comments personally.

It was difficult to read about the flaws in something I worked so hard on and took a long time for me to produce. However, my advisor wisely told me to step away from these comments and return to them in a week with fresh eyes. After carefully going through the reviews with my advisor, she told me that even though they can feel personal at first, our goal is to submit the best paper possible, and that it is important to try to separate these personal feelings from the work.

I sat down again and began to overhaul the manuscript. When I actually looked at them, the comments were fairly constructive, and I was able to significantly improve the original submission. However, I was a little more nervous about submitting it this time.

The next response I received was not a rejection, but one requesting major revisions, which my advisor and I took as good news, and a huge step in the right direction.

A meme from Dr. Brandon Jones's keynote presentation at the Atlantic Estuarine Research Society Spring 2018 meeting illustrating how peer-review criticism can feel. Credit: Brandon Jones

I have since resubmitted the revised manuscript addressing the reviewers’ comments, and I can honestly say that I feel like the science and writing is the strongest in this most recent version. I have not yet heard back from the journal, but when I do, my goal will be to make the manuscript better, whether or not it calls for major or minor revisions.

Although these rejections initially made me feel a little bit like failure, a quick Google search proved that most scientists have experienced these rejections, across multiple stages of their careers. I originally thought this was a sign that I did not have what it took to be a researcher. After talking with my mentors, I realized that my success is determined by how I choose to respond to this criticism, and I chose to persevere.

I now recognize that these rejections are not meant to be the endpoint for the research, but are rather an opportunity to make a more interesting and scientifically sound paper. Furthermore, I have learned more about the process of writing a manuscript. I have begun working on my next manuscripts, and I feel like I have a better idea of what may be a red flag for a reviewer and how I can more clearly defend the research. Rejection is always going to be a part of life, and I feel this lesson was a valuable one to learn as a graduate student. It motivated me to make something better, and ultimately proved to me that I do have what it takes to be a researcher.

Photo, top: Emily pulling a boat during field work because the Susquehanna Flats are too shallow to motor through the seagrass bed. Photograph, Cassie Gurbisz

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog