Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Applying New Skills for National Science Collaboration

Some would call flying to New Orleans on Mardi Gras a fool's errand, but on February 21, 2023, I did just that. Instead of joining in on the festivities, I was there to help lead an aquaculture workshop. Earlier that morning, I had arrived sweaty to Ronald Reagan National Airport, lugging a 45-pound suitcase filled with extension cords, flipchart stands, a video conferencing camera, and countless cords and cables from my home in southern Maryland. A second suitcase arrived at the airport soon after I did, under the guardianship of my boss and the director of Maryland Sea Grant, Fredrika Moser. A flight and a few hours later, we landed in Louisiana.

When I graduated in 2021 with degrees in marine science and zoology, I knew I wanted to find a way to use my knowledge and experience to benefit communities and address challenges related to climate change. The science management and policy internship at Maryland Sea Grant was the perfect opportunity to place myself exactly where I wanted to be: at the intersection of science and real-world application.

Soon after I started, I joined a project that is a partnership between Maryland Sea Grant and NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science (NCCOS). The project focuses on progressing sustainable aquaculture in the United States by building capacity among those involved or impacted by the aquaculture industry. I was eager to learn more about aquaculture, a topic I did not have a lot of background knowledge on. I soon learned that aquaculture is key to building resilient communities in the face of climate change, a part of Maryland Sea Grant’s mission.

Aquaculture is an alternative to traditional fishing and harvesting practices and is used to grow a variety of seafood, including shellfish, finfish, and seaweed. Aquaculture has steadily increased since the mid-1900s and now accounts for more than 50% of global seafood production. However, the United States has not kept pace with this increase and still relies heavily on seafood imports. About 70-80 percent of seafood consumed in the US is imported. The US Congress has recently taken efforts to sustainably increase seafood production, which means conversations on how to expand aquaculture are happening throughout the nation.

One of the most important parts of the conversation is aquaculture siting, meaning where to put aquaculture farms. Some farms are land-based but many are in open waters in marine environments. While at first glance it may seem like there is plenty of space in the ocean for these farms, the waters surrounding the United States are buzzing with activity. A lot of space is reserved for other uses, including shipping, military, energy production, fishing, recreation, and conservation. It leaves little space left for aquaculture farms. Additionally, much like how the right climate and soil conditions are important for land-based agriculture, certain ocean conditions must be met to grow seafood.

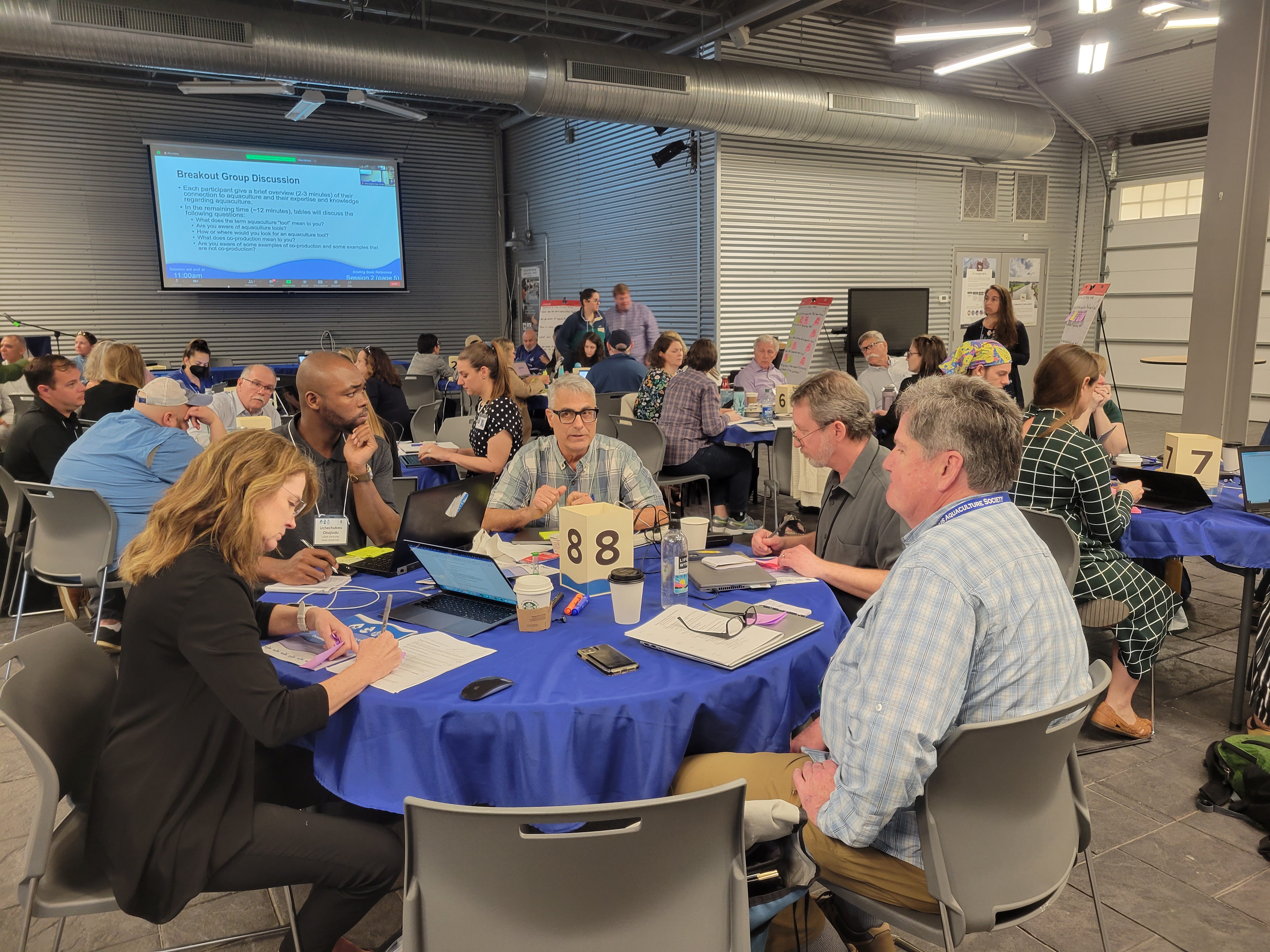

NCCOS has developed several tools that help identify suitable places for aquaculture farms in marine environments. They have partnered with Maryland Sea Grant and the National Sea Grant Office to learn how farmers, regulators, nongovernmental organizations, and others use these tools for aquaculture siting in the US. We are hosting six regional workshops to connect with aquaculture and fisheries industry members, state and local governments, nonprofits, and academics to learn about the status of aquaculture in the US and varying approaches to siting offshore aquaculture.

Originally, I was brought onto the project to brainstorm how to reach new audiences who are interested in aquaculture and how the workshops could address equity and inclusivity in aquaculture. I soon took on the additional responsibility of planning and coordinating the workshop in New Orleans, focused on aquaculture in the Gulf of Mexico region. I was nervous at first that I did not have the expertise in aquaculture, but I was excited for the opportunity to learn on the job.

Leading up to the workshop, I curated the agenda and briefing materials, coordinated registration, and recruited presenters. We worked with Sea Grant and NCCOS partners in Florida, Texas, Mississippi, and Alabama. It became evident that in a post-pandemic world, a hybrid option for the workshop was not only encouraged but expected. However, the going rate for on-site IT support for a hybrid meeting is several thousand dollars, which exceeded our budget. Eyes turned to me. I do not have any training in A/V systems but growing up alongside the technology boom of the early 21st century, I felt up to the task.

The day of the workshop was a blur. I was bouncing around the room making sure everything sounded okay, that the Wi-Fi was working, and that our speakers’ presentations were loading properly. All the while, I was communicating with my colleague Jenna Clark, who was back in Maryland running the Zoom meeting for our virtual participants. When 4 p.m. rolled around, I breathed a sigh of relief. We had finally made it through the eight hours that had taken months of preparation. We were getting great feedback from everyone in the room, and all the project partners seemed happy with the day.

In the time since the Gulf of Mexico workshop, we successfully hosted another workshop in San Diego, California. Now, we are preparing for a workshop in Alaska. I have learned a tremendous amount about how to develop project goals, implement workshops, and adapt to shifting priorities and project demands. Even though aquaculture is not my main area of interest, I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity to work on a project that is relevant to the environmental and economic health of communities throughout the US. I am eager to apply the skills and knowledge I continue to develop through this project to my future endeavors.

Top left image: Left to right: Fredrika Moser, director of Maryland Sea Grant; Bill Haines, board member for the Meraux Foundation who donated the space for the workshop; and Hannah Cooper

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog