Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Scientists Investigate a Salamander’s Defense Against Deadly Fungal Disease

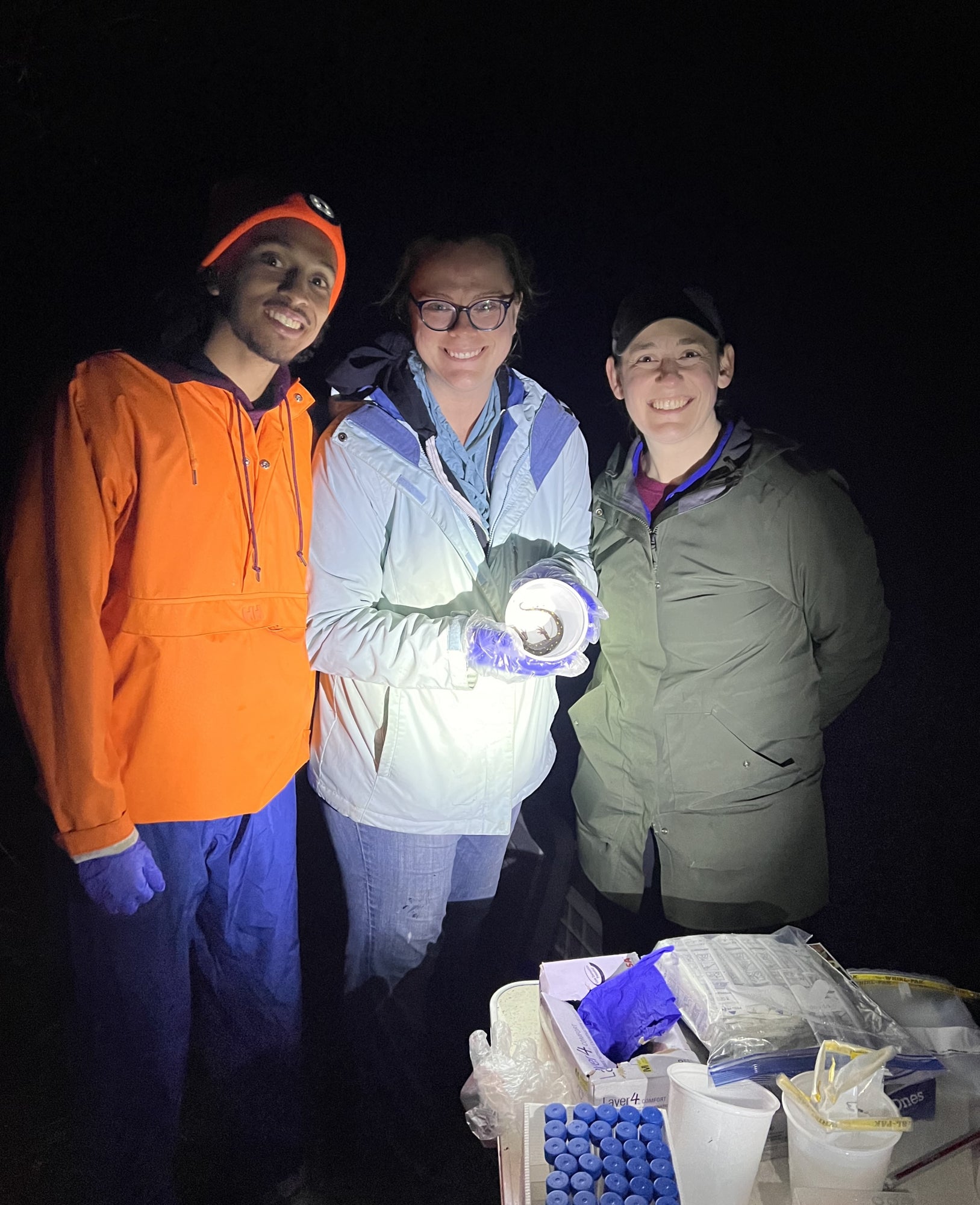

In a dark forest, Julian Urrutia-Carter lifts a baggie from a folding table. The liquid inside sloshes gently as he raises it to his eyes, his headlamp illuminating the small, wriggling amphibian inside. As a research fellow with Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, Urrutia-Carter is studying the spotted salamander’s resistance to a deadly fungal disease. But this is the first time he’s seen a spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) up close.

Spotted salamanders are a rare sight, even in the woods where they live. They are a species of mole salamander and spend most of their lives in underground burrows. Once a year, they emerge and travel through the night to seasonal ponds, called vernal pools, to breed. After just a few days, they return to the forest where they’ll remain hidden for another year.

J. Adam Frederick, Maryland Sea Grant’s assistant director for education, has spent years tracking spotted salamander migrations in Frederick County’s Municipal Forest. He volunteered to help the researchers find the salamanders they would need for their study.

The Chytrid Conundrum

In the 1990s, amphibians in Australia and the Americas were experiencing mass die-offs. The culprit? Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd. This aquatic fungus causes Chytridiomycosis, an infectious disease known for its devastating impacts on amphibians, earning it the nickname “amphibian chytrid.” In 2013, scientists identified a second deadly chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans, or Bsal.

“[Bd and Bsal] are closely related, and they’re the only chytrids we know that infect vertebrates,” says National Institute of Standards and Technology microbiologist Carly Muletz Wolz. They thrive in the same cool, aquatic environments as amphibians, and they feed on keratin. “And amphibian skin is packed with keratin,” says Urrutia-Carter.

Yet, there are some amphibians that show a surprising resistance to chytrid, like the spotted salamanders found in Western Maryland’s Appalachian Mountains. Understanding the mechanisms of Bd and Bsal resistance in salamanders could help scientists respond if Bsal comes to the Appalachians, or if a more virulent strain of Bd arises.

Salamanders have a layer of mucus they secrete from their skin. They also have a unique skin microbiome—a complex living collection of microorganisms like bacteria, fungi, and viruses collected from the environment. "You could find a red-backed salamander, a two-line salamander, or a spotted salamander all under the same log, and they would all have different microbes," says Muletz Wolz.

Because chytrid is a skin pathogen, could the clue to the spotted salamander’s resistance reside in its microbiome or mucus secretions? On a cold night in March 2024, Urrutia-Carter and a team of Smithsonian researchers set out to unearth salamander secrets.

Into the Woods

The air was thick with fog as the team gathered at the outskirts of Frederick County’s Gambrill State Park shortly after sunset. Somewhere above, the clouds released a steady drizzle of rain. “It was almost like a ghost town,” says Urrutia-Carter. “But it felt like the perfect conditions. If I was a salamander, I’d love to be out there.”

The researchers took inventory of their supplies before setting off down a long gravel road. Frederick led them deeper into the woods, headlamps winking in the fog. Soon, the trees thinned, revealing a large clearing with a shallow pool of water. The researchers fanned out around the vernal pool to begin their search. “Over here!” someone shouted, gesturing for the others to follow. The dark water, illuminated by a flashlight beam, swarmed with brightly spotted salamanders. “That’s when the fun started,” says Urrutia-Carter.

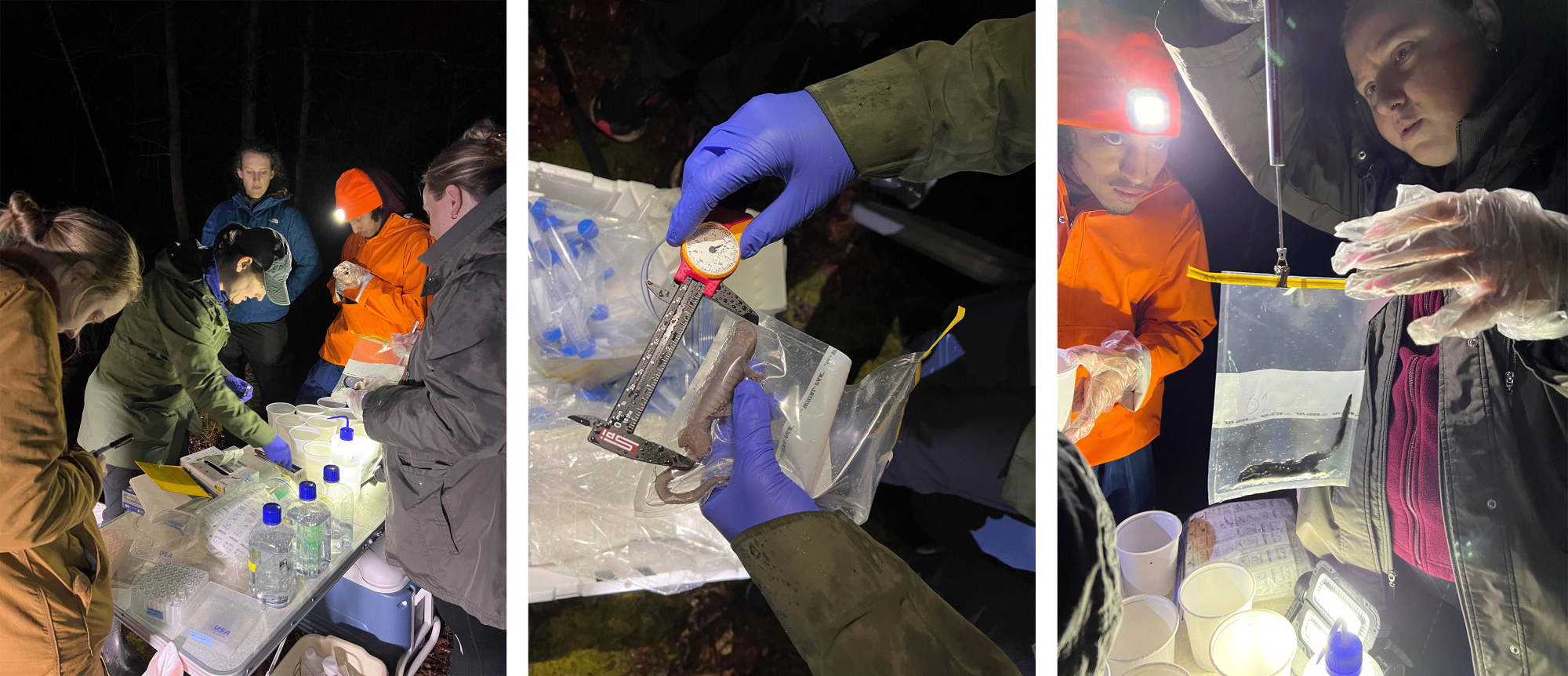

The researchers spent the next few hours collecting salamanders from the pool and delivering them to a makeshift field station—a folding table with swabs and vials, bags of clear liquid, measuring tools, clipboards, and coolers.

They measured, weighed, and sexed each salamander and took a swab of the microbes on their skin. Then, they let each salamander soak in a water bath to collect the chemicals and peptides produced by the skin’s mucus secretions. One by one, the researchers released the salamanders back into the vernal pool.

Back in the lab, the team waited to see what their samples might reveal about the spotted salamander’s chytrid resistance. They used DNA sequencing methods to identify the bacteria in the salamander’s skin microbiome. “We’re actually picking up the DNA [the bacteria] left behind on the salamander skin and saying, if we look at your DNA, what species are you?” Muletz Wolz explains. The researchers compared what they found to a database of thousands of bacteria known known to inhibit chytrid.

The researchers had also hypothesized that something in the salamander’s mucus secretions may provide resistance to Bd and Bsal. They cultured chytrid zoospores alongside their water bath samples to see if the skin secretions would kill the pathogen. Zoospores are the free-swimming spores produced by the chytrid fungus that move through the water, looking for a new host to infect. “Surprisingly, those skin secretions did nothing,” says Muletz Wolz. And while the team did find some defensive bacteria in the spotted salamander’s skin microbiome, it was not enough to indicate that the microbiome is key to chytrid resistance either.

Adjusting the Lens

Still, these findings are important, says Urrutia-Carter. Ruling out these mechanisms of chytrid resistance helps narrow the search for what does protect spotted salamanders. And it points researchers toward new possibilities, like other physiological defenses or environmental factors.

Spotted salamanders are difficult to find outside of their brief spring breeding window, so perhaps a clue to their chytrid resistance is present during a different life stage. Muletz Wolz says future work could explore the spotted salamander’s immune cell responses or could involve the complicated task of conducting broader sampling of the animals across regions and seasons.

“These problems are fun to try and solve,” says Urrutia-Carter. He is now a visiting researcher at the University of Michigan. “There’s always something to look forward to learning more about.” For now, the spotted salamander’s chytrid resistance remains an ecological mystery, but unraveling it could support the conservation of amphibians around the globe that don’t show the same resistance to Bd and Bsal.

Curious to learn more about spotted salamanders? Check out our December 2025 issue of Chesapeake Quarterly magazine. Follow Maryland students as they raise spotted salamanders in the classroom, getting an up-close look at amphibian development and the unique symbiosis between salamander embryos and green algae.

See all posts from the On the Bay blog