Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Founding Treasure

Fisheries science professor Tom Miller had his hands full as director of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s Chesapeake Biological Laboratory when an engineer reported that cracks in Beaven Hall made the building unsafe. It needed to be vacated immediately. The oldest state-funded building on the Solomons Island campus, Beaven was built in 1931 and housed administrative and staff offices, but more significantly, the historic campus’s library.

Located on the second floor, the library’s sheer weight was affecting the building’s structural integrity, so staff needed to remove all library materials until the building was repaired. Toward the end of the job, Miller was clearing the former librarian’s office when he tackled a windowsill-high pile of stuff in a corner. Rummaging to the bottom, he found a curious, nondescript cardboard box. “It had ‘Do Not Crush’ written on it,” he says, “And it was being crushed by the weight of books and journals and precious materials of some kind that had been on top of it for 20 years or more, I’d imagine.”

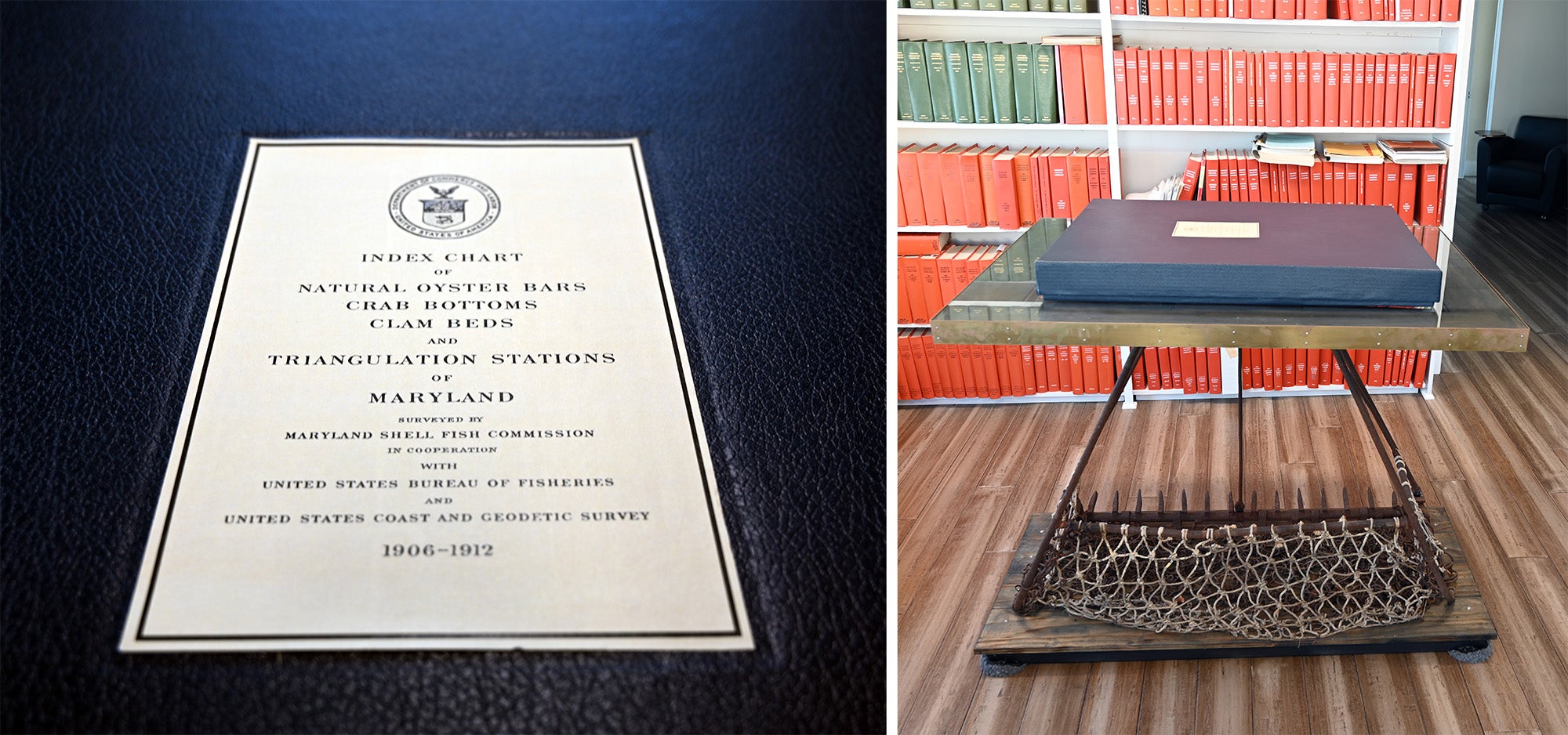

Inside, he found a time-warp treasure—a complete edition of the Charts of Maryland Oyster Survey 1906-1912, colloquially known as the Yates Bars book. “Even more surprising was that the inside cover of the book had been signed by [Reginald V.] Truitt, the man who founded the lab in 1925. So it was a book he had bought for the lab, one of the first books the library had,” Miller says. At nearly four feet long when fully opened, and almost three feet wide, it was a massive folio.

“You can see sort of coffee stains on the pages where people had been planning cruises around the Patuxent River and areas around Chesapeake Biological Laboratory over the years; you can see pencil marks and erased pencil marks,” he says. “It was a well-loved book.”

But it was also in delicate shape, with binding damage and mildew on some pages. After consulting with a book restorer in Washington, DC, Miller and his wife paid about $5,000 to have the volume refurbished and rebound. Each page is bonded to heavy-stock linen backing paper, enabling the book to still be used as intended—a definitive survey of Maryland’s natural oyster bars, clam beds, and crab bottoms, mapped and drawn by hand.

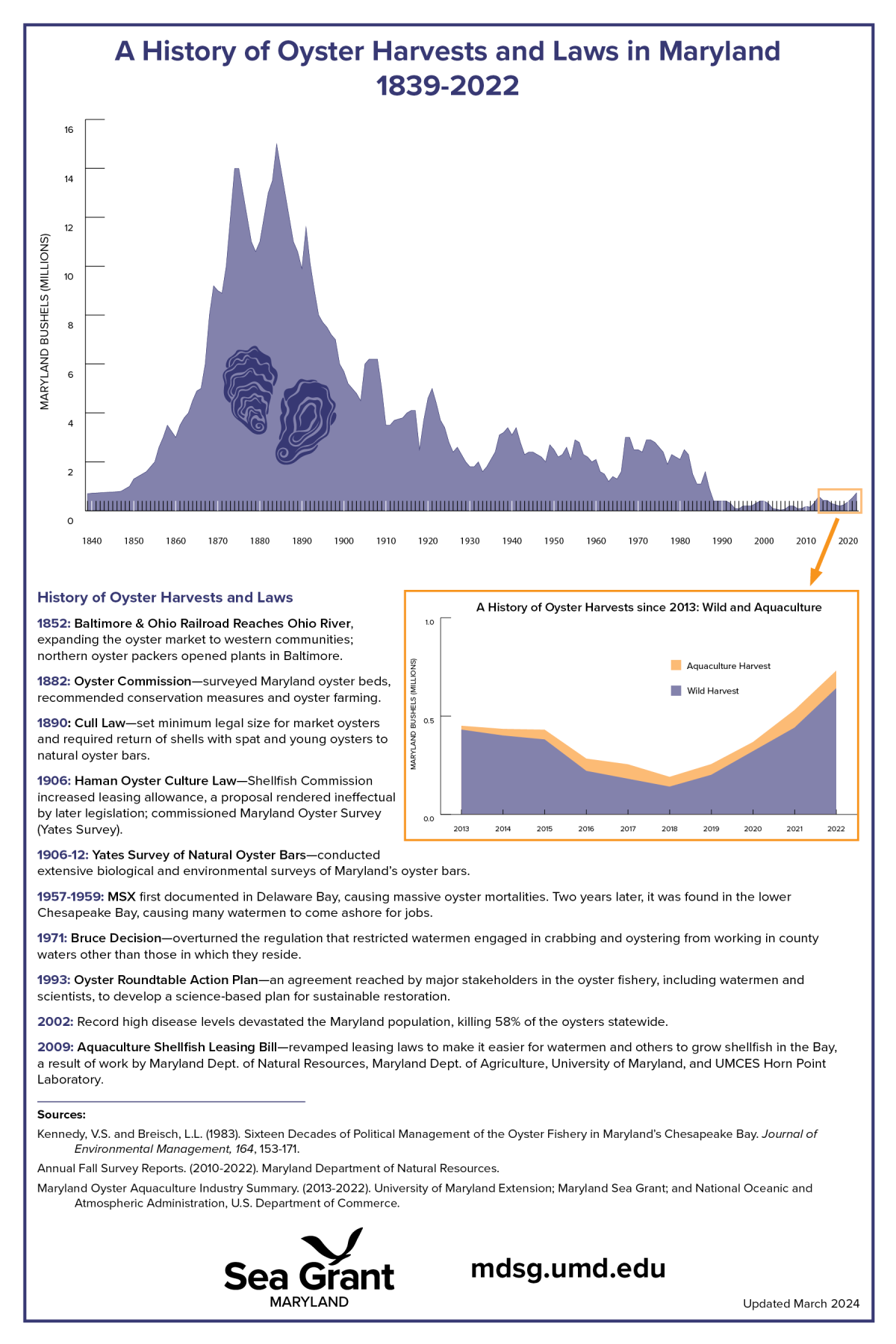

The Yates Bars charts are the result of the Oyster Wars in the late 1800s and the alarming depletion of the fishery. In 1906, watermen pulled 4.5 million bushels of oysters from Maryland’s natural oyster bars. This seems an astronomically high number today, but at the time it marked a severe downturn from a peak harvest in 1884 of 15 million bushels.

“By 1906, the yield from the Natural Oyster Bars had fallen so far below the mark that there was a general demand from citizens of the State for the enactment of measures for the conservation and development of the oyster resources through cultivation,” writes Gary F. Smith in Maryland’s Historic Oyster Bottom: A Geographical Representation of the Traditional Named Oyster Bars, a report outlining a 1997 digital mapping project by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and Oxford Cooperative Laboratory.

Before 1906, leases were demarcated by metes and bounds—an old English measurement system brought to the colonies that eventually formed the United States. This method often led to “complex and legal (or extralegal) boundary squabbles,” Smith notes.

So-called barren bottoms were areas where oysters didn’t grow abundantly enough to support watermen’s livelihoods. That didn’t mean, however, they couldn’t potentially support oyster growth, so they were selected as areas for leased aquaculture. Natural bars, on the other hand, were to retain their historical “commons” status for everyone to use.

“To make the leasing of barren bottoms possible, and leasing of natural oyster bars impossible, the Haman Oyster Culture Law [passed in 1906] provided for a survey of the natural oyster bars for the purpose of accurately locating and marking them,” Smith’s report says. “In effect, oyster aquaculture could exist in the Maryland bay, but not where oyster harvest was possible.”

The survey began June 25, 1906, and ended September 27, 1911. It was led by Captain C.C. Yates of the US Coast and Geodetic Survey. His name—inked in bold, handsome cursive throughout the pages—continues to be used today to denote these historic charts and oyster bars.

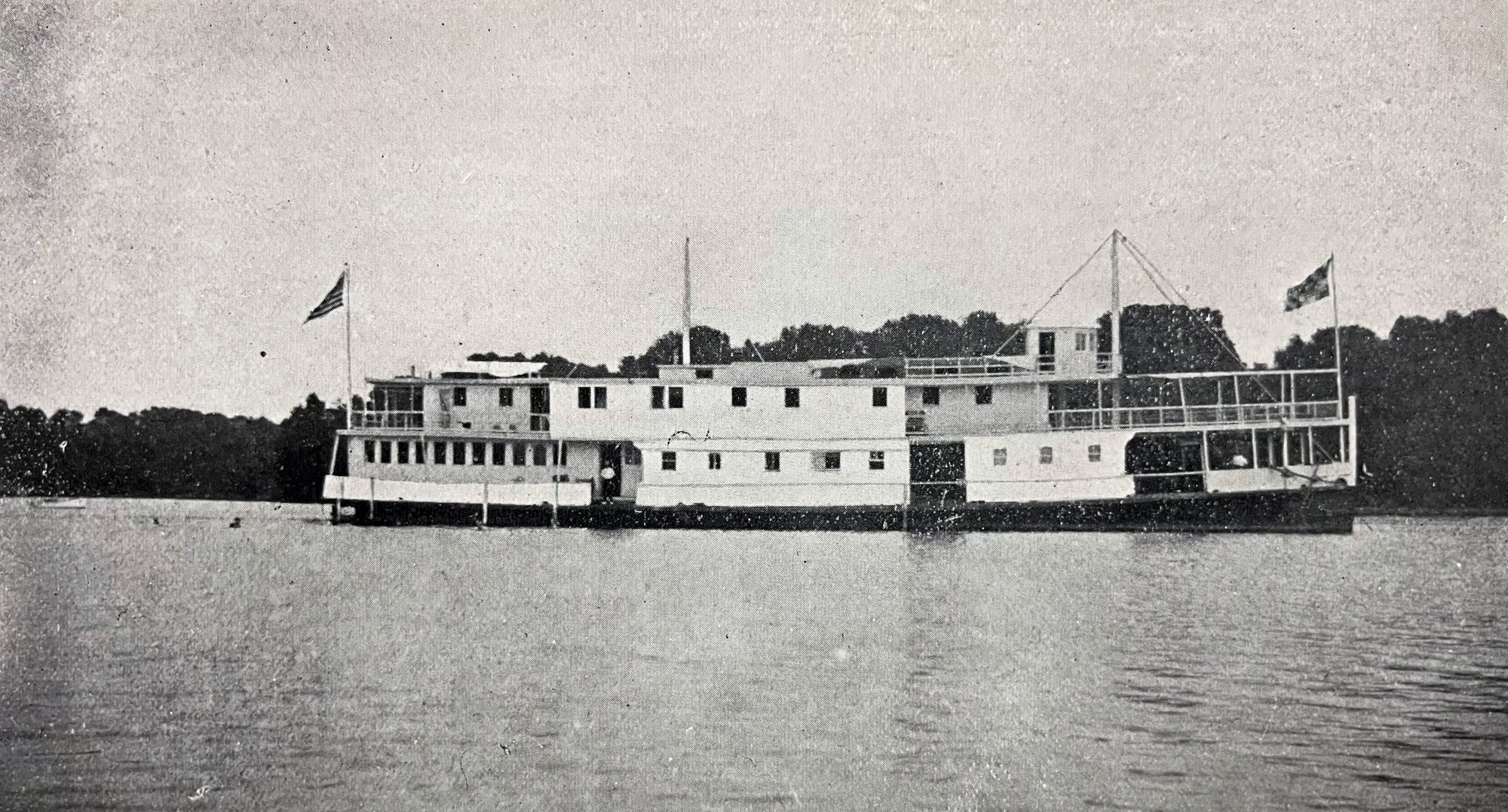

Born in 1868, Charles Colt Yates commanded survey vessels all over the world, from the Philippines and Hong Kong to Bermuda, Alaska, and the Caribbean. In the Fourth Report of the Shell Fish Commission of Maryland, published in 1912, the authors repeatedly lauded Yates for his cooperation and dedication. “His interest in the work was not confined to the problems of triangulation and chart making, but extended actively to all that pertained to the oyster interests of Maryland,” they noted. “If, as has been said by those who are in a position to judge, the oyster survey of Maryland is the best of its kind ever made, much of the credit belongs to Captain Yates…very early in the survey he ‘nailed to the mast’ of the Houseboat [Oyster] the motto, ‘A survey or investigation that does not end in proper legislation is a failure,’ and no one lost sight of this objective.”

The surveyors lived aboard the Oyster, formerly the Thomas L. Worthley, a 135-foot sidewheel steamer that was converted for the purpose. Yates noted that the main deck had accommodations for 27 men, the officers’ mess, and the galley. The second level had 11 staterooms for officers and engineers, as well as “a drafting room, a laboratory for oyster investigation, and an office room.” When complete, the surveying “field party” numbered 20 men, among them two cooks, two waiters, two oarsmen, a machinist, an expert tongsman, a draftsman, a clerk, and a leadsman who took soundings.

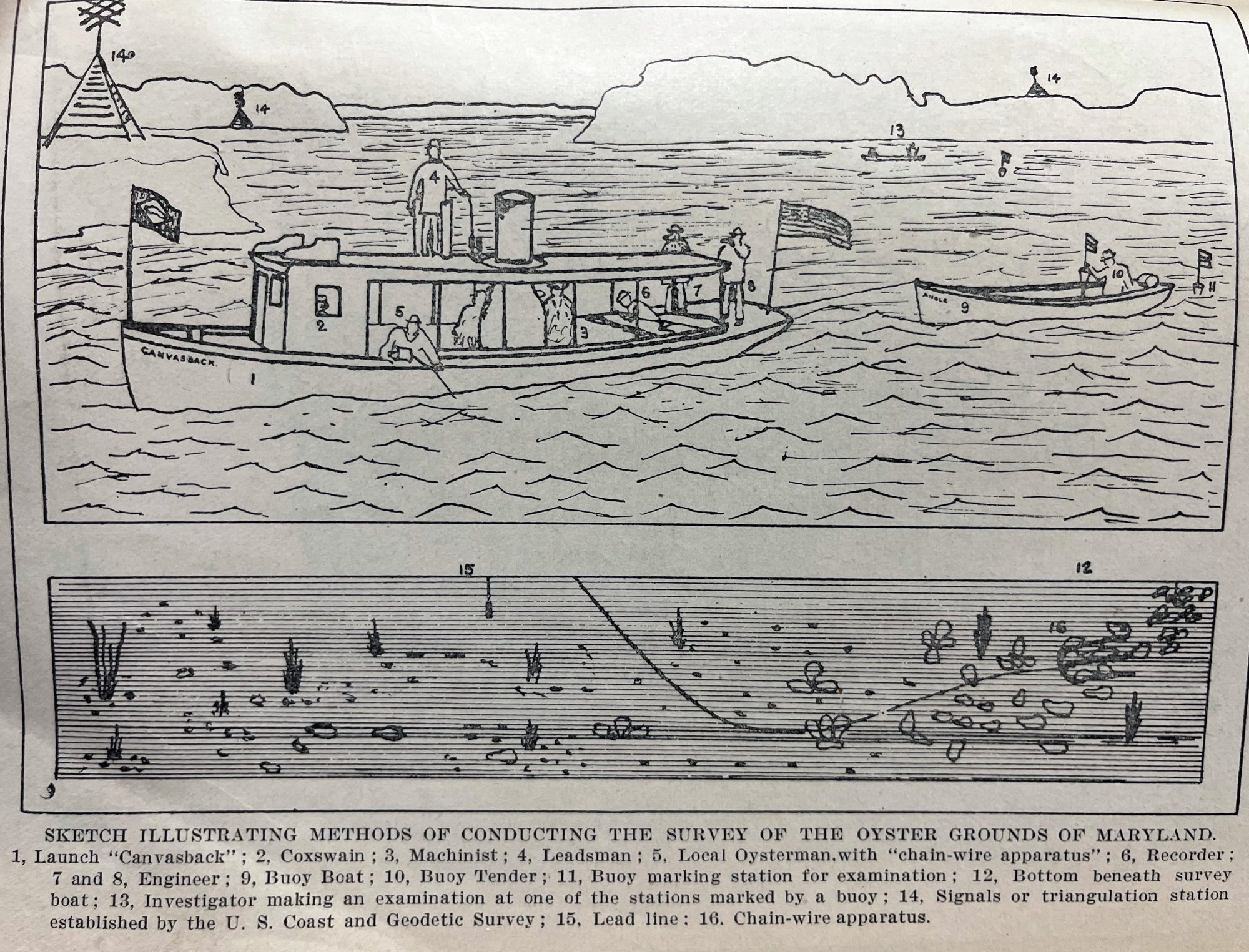

Surveyors used multiple vessels, including the 42-foot launch Canvasback, the 24-foot bateau Angle for shallow work, the steam launch Inspector, the coal launch Blake, the 32-foot scow Maryland, and the state steamer Governor R.M. McLane, “for surveying in the bold waters of the Chesapeake Bay.”

“Local assistants”—oystermen—from each county were also part of the team, identifying the approximate locations of the natural bars. They also provided the bars’ names, which ranged from the obviously practical—such as the 3,292-acre Swan Point Bar off Rock Hall’s Swan Point—to the whimsical, mysterious, and those that begged a backstory—for example, the 573-acre Old Woman in Annapolis Roads; the 1,348-acre Chinese Muds off Drum Point; and the 10-acre Jackass in the Rhode River.

Once over a bar’s approximate position, the Canvasback team would run “a zigzag or parallel series of lines” over the area, recording depth and bottom characteristics to determine its limits. The choreography was precise—a bell prompted the leadsman to take a sounding every 20-30 seconds, as the recorder noted his findings. At the same time, the “local assistant” operated “the chain-wire apparatus”—a piece of heavy chain dragged along the bottom and attached to a copper wire. Holding the wire as the chain passed over the bottom, he could feel the vibrations indicating the bottom’s nature and density, which he announced immediately after the soundings at each interval—barren, very scattering, scattering, medium, or dense.

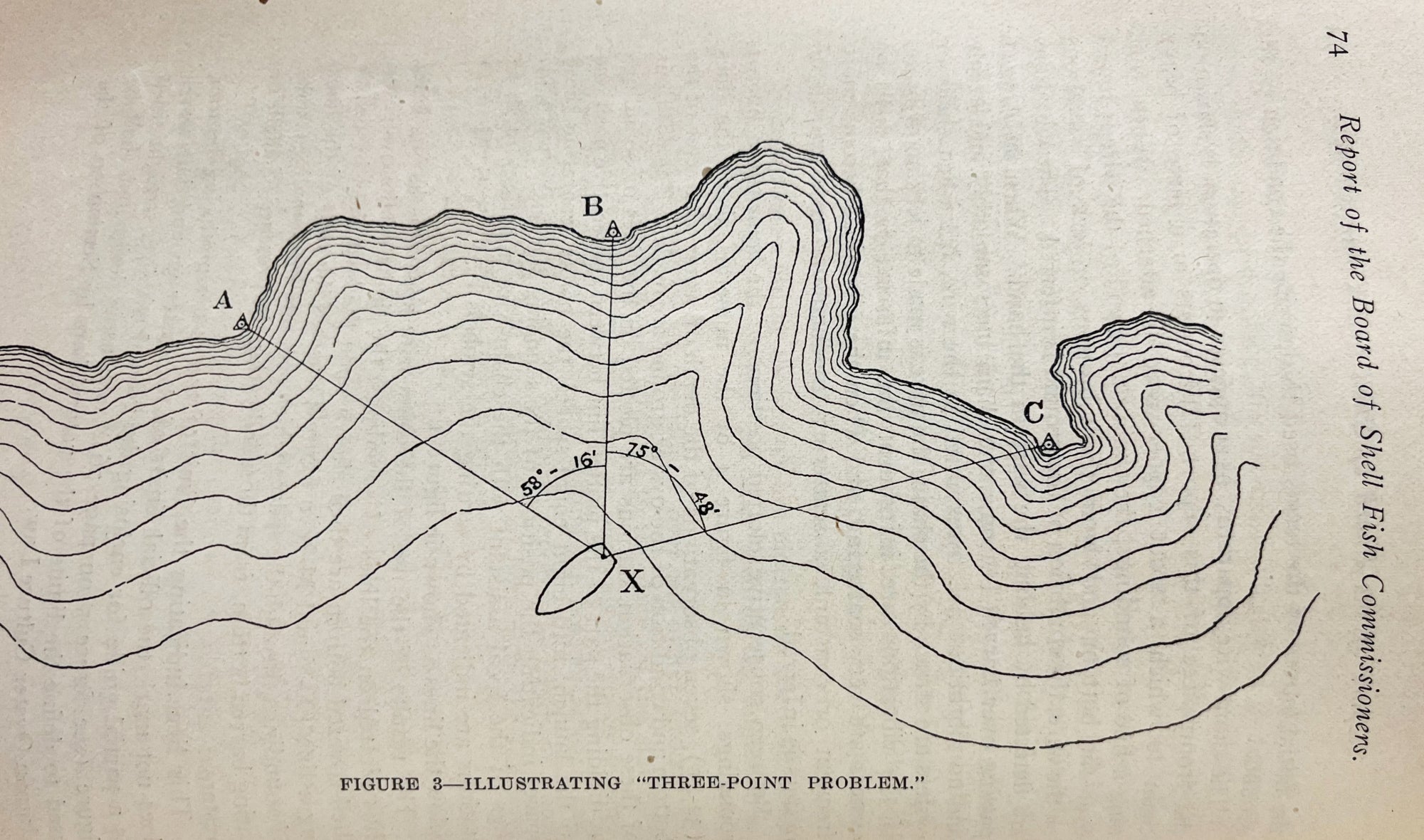

Using sextants to triangulate the launch’s location with positions on land—stations denoted on the charts as a circle enclosed in a triangle—the bars were mapped as straight-sided shapes containing name and acreage. The surveyors also mapped bottom type: sand, mud, shell.

Marshy areas are denoted by tiny tufts of grass, clamming beds outlined with asterisk-like symbols. Water depths and contours are revealed in a series of dotted and dashed lines defining depths between six and 60 feet. Running throughout the rivers and down the wide lengths of the Bay, these are like elegant strands of tiny pearls juxtaposed to the hard, straight edges of the oyster bars.

The charts’ detail and precision reflects a prodigious amount of skill, time, and effort, Miller says, noting that they were created in a time before aerial surveys.

“When you think about the phenomenally high standard that mapping these bars required, and the dedication of the people who did the work—not only the physical drawing and etching but the people who did all of the survey work—it stands as a testament to the quality and care and precision of the people who did the work. And I do think it also stands as a beautiful piece of art. It’s not creative in that sense, but there’s no doubt about the level of skill that was involved in creating these maps.”

The 1997 DNR report notes, “The original Yates Survey contained 779 named oyster bars within the Chesapeake Bay,” comprising 214,772 acres of Bay bottom. Talbot County listed the greatest number with 135 bars of 35,828 acres, and Dorchester second with 122 bars of 33,039 acres. Later so-called additions brought the number to 1,105 named bars comprising 329,977 acres.

The Yates Bars charts remained the standard until 1985, when subsequent surveys (which still used the Yates surveys as a baseline) remapped the natural oyster bars and eliminated the local names, opting for a numbering system. Nevertheless, the 1997 report notes, “Local watermen always did, and still do, refer to the oyster bars by their historic names, as do the field biologists who monitor the condition of the oyster beds. Because the named oyster bars are a more accurate depiction of where true oyster bottom once existed, they are much more useful for describing both harvest location and sampling positions than the newly numbered oyster bars.”

The report also extols the historical and cultural value of the original names preserved in the Yates survey. “Many of these names predate any collective memory, perhaps having originated in the colonial era. The names of the bars refer to persons, places, or things of long past importance. Names such as Old Woman’s Leg, Norman’s Fine Eyes, Roasting Ear Point, Daddy Dare, and Hollicutt’s Noose had meaning to some or many at one point in history. The names and their variations (e.g., Gough = Garf = Gorf = Garst; Willow Bottom = Winter Bottom; Bachelor Point = Bastard Point) could offer insights to etymologists and historians. They are a tradition worth preserving.”

For the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, the original Yates Bars folio signed by Reginald Truitt is equally valuable, Miller says. Now safely tucked into a box and kept on a purpose-built display table in the lab's library—the base of which is made from an oyster trawl that Truitt and the lab's staff once used—the 114-year-old volume is a direct link to the lab’s founding purpose.

“Truitt’s vision was to understand why crabs and oysters were declining,” Miller says. “And the fact that we have the volume that he bought to guide the work on oysters, and where they were and how abundant they were, to my mind makes it one of the founding volumes in our library and of fundamental importance to the identity of the institution.”

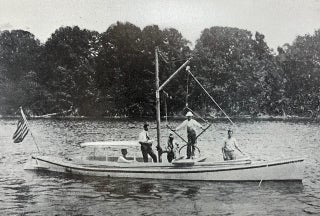

Top photo: The launch, Inspector, used in the Yates Bars surveys.

See all posts from the On the Bay blog