Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Tiny Powerhouses Shaping Our Future

Stepping into the Sant Ocean Hall at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History felt surreal—one of those rare moments when my work, my passion, and the world around me suddenly align. After walking past the iconic African elephant that greets millions of visitors each year and the Hall of Geology, Gems, and Minerals, just steps away and home to the Hope Diamond, I found myself standing beneath “Phoenix,” the life-size North Atlantic right whale model that anchors Sant Ocean Hall. I prepared to share a story most people have never heard, about how microorganisms found in oceans, lakes, soils, and even snow are shaping the future of biotechnology.

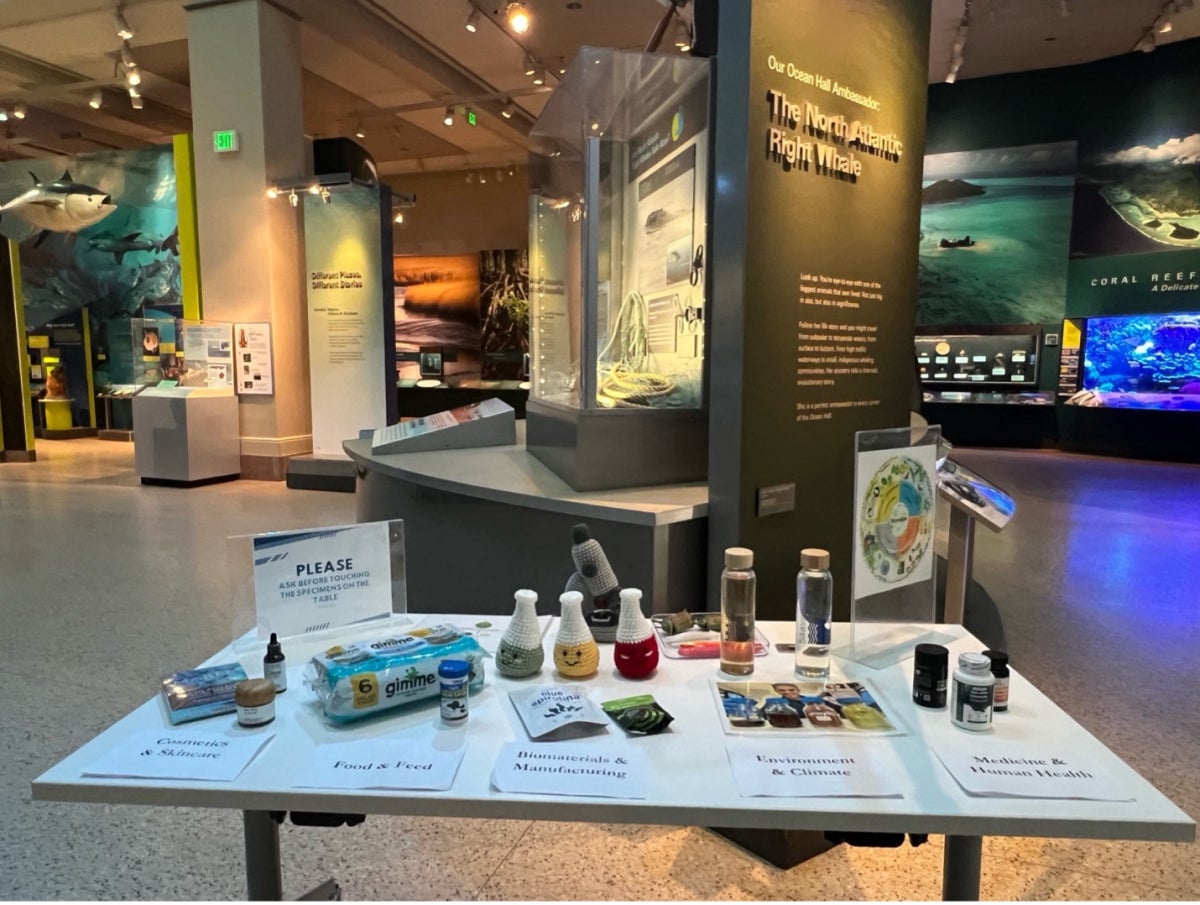

I was there for the museum’s “Expert Is In” program, wearing two hats at once: a scientist studying microalgal metabolism and a congressional science-policy fellow thinking about how these discoveries can scale to be real-world solutions.

My table wasn’t a lab bench. It was a visual story, organized into five themes that touch our daily lives: Medicine and Human Health, Environment and Climate, Food and Feed, Cosmetics and Skincare, and Biomaterials and Manufacturing. In each section, I highlighted familiar products and applications already connected to microalgae. These tiny photosynthetic organisms contribute to omega-3 supplements, superfoods, skincare serums, natural pigments, fuel, fish feed pellets, and even the health of entire water systems. Many people were surprised to learn that algae aren’t just green—they come in shades of red, orange, blue, yellow, and even black. These colors link to a unique compound with biological importance. Some visitors approached curiously and asked, “Wait… all of this comes from algae?”

Many conversations naturally turned to health, because people want to understand where these products come from. I explained that microalgae make colorful pigments like lutein and beta-carotene to protect themselves from harsh sunlight, and those same molecules help support human eye and vision health. Spirulina and chlorella, rich microalgae powders found in smoothies, supplements, and bodybuilding shakes, pack an impressive concentration of protein, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants in a small scoop. We talked about astaxanthin, a powerful red antioxidant produced by certain microalgae, which turns salmon, shrimp, and even flamingos that famous pinkish-orange color after they eat algae-rich diets.

Many people are surprised to learn that while fish oil is extracted from fish, the key omega-3s in fish oil are made by microalgae at the base of the marine food chain. Fish mainly accumulate them by eating algae. Producing omega-3 directly from microalgae reduces pressure on wild fisheries and provides a clean, traceable source of these essential fats. Those moments helped people see microalgae not as a passing trend, but as a smarter, more sustainable foundation for future nutrition and medicine.

From personal health, the conversation easily expanded to planetary health. Photosynthetic organisms in the ocean produce roughly half of the oxygen we breathe. Notably, they have been climate heroes since the beginning, helping to oxygenate early Earth and producing a significant share of the oxygen we breathe today. They absorb carbon dioxide and convert it into new biomass and oils. In my research, I’ve studied how microalgae shift their metabolism when grown on carbon sources such as glucose and acetate, thereby increasing the amount of lipids (natural oils and fats) they store. Those lipids can be refined into renewable fuels or tailored for different uses. With genetic and metabolic engineering, we can program microalgae to produce various types of oils. Some could be used for cleaner fuels like diesel or jet fuel, and others could be used as renewable oils for products and manufacturing.

What’s especially exciting is how algae grow. They can use waste carbon dioxide from factories and nutrients from wastewater or runoff. That means they can act like living treatment plants, soaking up excess nitrogen and phosphorus before those nutrients cause pollution downstream. By reducing nutrient overload, they support healthier soil and water conditions.

As people began to understand algae as environmental partners, they naturally asked whether we eat them too. Many visitors were already familiar with seaweed in sushi or soups and were surprised to learn that those are macroalgae—larger leafy relatives of microalgae. While seaweed plays an important role in global diets, microalgae are also becoming increasingly valuable in food and feed, often in more hidden ways. The brilliant blue color in some smoothies and candies, for example, often comes from phycocyanin, a natural pigment extracted from spirulina, rather than a synthetic dye. Some plant-based protein drinks, snacks, and nutrition bars include microalgae to boost amino acids and micronutrients while using minimal land or fresh water. In aquaculture, microalgae are essential feed for young fish and shrimp, helping us grow seafood without relying solely on wild-caught fish for food and fish oil. In a warming world with limited arable land, microalgae offer a flexible way to add nutrition to both human food and animal feed.

Skincare and cosmetics added another relatable dimension to the story. When I told people that microalgae spend their lives facing the very stresses our skin endures—strong sun, dryness, salt, and pollution—they immediately understood why algae produce such potent protective compounds. To survive, microalgae make antioxidants, UV-absorbing molecules, and sugars that help them hold onto water. Those same ingredients are now being used in facial oils that support the skin barrier, hydrating masks that calm and brighten, and gentle scrubs made from finely extracted algae instead of plastic microbeads. For many visitors, it was reassuring to know that their skincare can be both science-driven and environmentally conscious, swapping out ingredients for those grown sustainably.

The final leap, biomaterials and manufacturing, took people straight into the future. Microalgae can be cultivated for oils, pigments, and biopolymers produced inside their cells, which can then be used to make biodegradable plastics, packaging, inks, and natural fabric dyes. Designers are experimenting with algae-based pigments to color textiles without harsh synthetic chemicals, and engineers are exploring algae-derived resins for films, coatings, and even early 3D-printed parts. Everything on my table tied back to a simple idea: the things we use every day don’t have to come from finite and nonrenewable resources. With thoughtful investment, engineering, and supportive policies, microalgae-based materials could help reduce plastic waste, cut emissions, and build new industries rooted in renewable biology.

Looking ahead, microalgae sit at a frontier of innovation. They could help reshape how we tackle climate and sustainability through wastewater cleanup and nutrient recovery, carbon capture, lower-carbon aviation fuels, and cleaner manufacturing. And the opportunity isn’t only scientific—it’s entrepreneurial. Algae biotech offers a wide runway for innovation and scale-up, opening the door to new products, processes, and supply chains, including circular systems in which waste carbon dioxide and excess nutrients become feedstocks for valuable oils, proteins, and other high-value compounds.

Reaching that future, though, takes more than great science. It takes the whole ecosystem—policies that support pilot projects and next-generation facilities, partnerships that connect research to engineering and industry, and public awareness that turns “wow” moments into real momentum. As I experienced, once people see what algae have already done for our planet, it becomes easier to imagine what they can do for our future. A key take-home message is that science shows what microalgae can do; policy helps ensure they actually get the chance to do it.

Walking out of Sant Ocean Hall after my session made me feel deeply grateful for the chance to communicate my knowledge with the public while wearing my two hats. Microalgae shaped our past, define much of our present, and with thoughtful effort, can help us build a cleaner, more resilient world. The future will not be shaped by size but by intention, and microalgae prove that even the smallest living things can make a tremendous change.

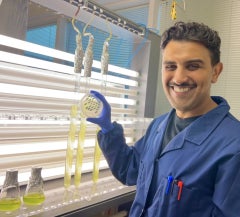

Top photo: Alrefaie holds up a petri dish containing thousands of colonies of microalgae grown on agar media. Scientists use these plates to isolate and study strains of specific microalgae variants under controlled conditions.

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog