Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

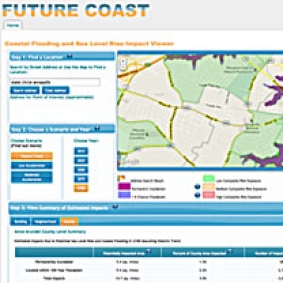

A Picture Tells the Story of Future Coastal Flooding

Researchers explore new tools to raise public awareness, discussion of sea level rise

Seeing -- and listening -- really does equal believing when it comes to public understanding of the sea-level rise that threatens communities along the Chesapeake Bay. That’s the finding of a recent experiment that tested an interactive, online map and other new ways of showing Marylanders who live by the Bay just how real may be the threat of increased coastal flooding from rising seas.

A research team led by George Mason University developed new educational tools that they hope may help Marylanders to understand and prepare for the flooding threat. And earlier this year, they tested these tools with residents of Anne Arundel County. The results of the project, titled Future Coast, showed promise.

Getting people to pay attention to this topic is inherently challenging: The water level in the Bay and the world’s oceans is predicted to rise gradually during this century and so on a year-to-year basis can be easily ignored.

In a pilot study to test the scientists’ new educational methods, the researchers invited 40 residents of Anne Arundel County to a day-long forum in late April at Severna Park High School. The residents were asked to view the interactive map, created by the research team, which predicts what sections of the county may be vulnerable to worse flooding in coming decades.

The map is unusual because it offers a lot of detail at the neighborhood level. It displays a numerical risk of flooding in different neighborhoods and describes whether the damage to buildings there would be minor, moderate, or severe. For example, zoom in on the U.S. Naval Academy, in Annapolis, and you’ll see that it faces by the year 2100 a significant chance of being flooded, with damage predicted to be moderate.

Participants in the forum were also invited to ask questions about coastal flooding and sea-level rise to leading Maryland scientists and policy makers who attended the meeting.

Finally, the residents broke into small groups to discuss the topic. Huddled around conference tables in the high school’s cafeteria, and assisted by trained facilitators, the participants were asked to try to forge consensus about difficult public-policy choices to respond to the flooding threat, such as how to spend limited government money. Should the county, for example, build more sea walls to protect coastal marshes, which play an important ecological function? Or instead spend that money to safeguard built-up, downtown commercial zones? The facilitators told them that there were no right answers.

To better understand the effectiveness of these educational techniques, the researchers polled the residents before and after the event to find out whether the map and the conversations had affected participants’ views. And in results released this week, the answer was yes. The poll respondents were significantly more likely afterwards to label sea-level rise a growing threat to the county, and fewer said they had no idea about when increased flooding could begin. The researchers have posted material from the forum here. If you live in Anne Arundel County, you can check out what the map shows about your own neighborhood’s risk of flooding, and you can watch videos of the Q-and-A at the forum. (You can also take a quiz to test your own knowledge.) The map and accompanying materials should be of interest to anyone who would like to know more about sea-level rise in Maryland.

Other poll results indicated that the participants came away from the forum with higher self-confidence about diving into a thorny public policy issue like sea-level rise. “That was good to see,” said Karen Akerlof, a Ph.D. candidate at George Mason and the project’s manager.

Some of the participants said that they also developed a better sense that doing something about coastal flooding would be necessary — but difficult. “Short-term solutions aren’t going to work as time goes on,” said Richard Havel of Crofton, Maryland. He got a first-hand lesson about that when his brother-in-law’s house near the Bay in Edgewater, Maryland, was flooded with several feet of water during Hurricane Isabel in 2003. So was downtown Annapolis. “I learned about the enormity of the problem and the futility of us, like little army ants, running around trying to put sandbags up to prevent it,” Havel said.

And Isabel may be a harbinger of things to come. Scientists say that the Bay’s water level could rise by 3.4 feet this century, in part because of a worldwide increase in sea level that is linked to climate change. (See in-depth coverage of "Ready for Rising Waters?" in Chesapeake Quarterly, Maryland Sea Grant's magazine.

The George Mason team hopes that other residents of Anne Arundel County and elsewhere in Maryland will begin new conversations about sea-level rise by using the materials on the Future Coast website. “That’s where we see our role, to help things along by providing the best available information in a format that’s useable,” said Todd La Porte, an associate professor of public policy at George Mason who was the project’s principal investigator. “We hope that the information will be used in all kinds of discussions — in homeowners association meetings, in schools. I can imagine [the map] becoming an interesting conversation starter for people.”

The project was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) through money provided to Mid-Atlantic Sea Grant, a consortium of state Sea Grant programs. Virginia Sea Grant administered the grant to the George Mason team.

Further information about sea-level rise and coastal flooding is available at NOAA’s Tides & Currents website. Maryland Sea Grant’s website also contains information about our program’s work on coastal flooding and climate-change issues in the Chesapeake Bay region.