Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

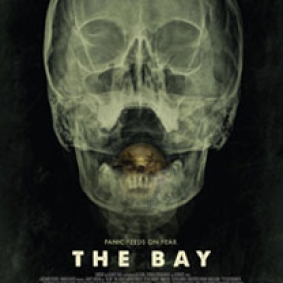

The Bay's Bad Guys?

The facts about the small crustaceans that wreak havoc in a horror film set in Maryland

Steven Spielberg had his great white shark, and Ridley Scott had his alien with acid for blood. But for Maryland native and fellow director Barry Levinson, the new fearsome villains are tiny, wriggling crustaceans in the Chesapeake Bay.

Don’t scoff. Levinson, who directed the cult favorite Diner, a coming-of-age tale set in Baltimore, has offered one creepy story in his latest film: The Bay, released in early November. In it, a small Maryland town on the Chesapeake Bay becomes ground zero for a strange epidemic of yucky skin infections. The cause, it turns out, isn’t a supervirus or a long-buried zombie curse. It’s isopods.

For the uninitiated, isopods are a type of small crustacean. Those roly-polies in your backyard that curl up when you poke them -- they’re isopods. Not exactly Jaws material.

But maybe that’s the point. Levinson has said in interviews (including this one in The Baltimore Sun that he intended the real bad guy to be poor water quality in the actual Bay. Not the invertebrates, however icky. (In the film, the Bay’s isopods have been mutated into killers by high levels of pollution in the estuary). Despite the ripped-from-the-headlines nature of the story, local scientists told The Sun in a second story that they weren’t impressed with the film. The consensus seems to be that Levinson, by showing too many bursting boils and too little science, missed the opportunity to bring serious attention to the Bay’s ills -- that includes the loss of wetlands and persistent summer dead zones.

Instead, the isopods are the de facto monsters of The Bay. In one scene, they’re shown crawling all over a fish, and one big one has even chewed the fish’s tongue off. It’s definitely squirm-worthy cinema. The question arises, however, do isopods deserve this bad rap?

Emmett Duffy, an ecologist at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), may be biased toward the isopods. For him, these animals are a natural, and even beneficial, part of the Chesapeake ecosystem. And they seem to be all over, residing in shallower waters and near the Bay’s bottom. Duffy, in particular, studies the organisms that live on and around eelgrass beds in the Bay. Many isopods live there, too, and they’re often grazers, he notes. That means that they tend to nibble on the microscopic algae that can blanket seagrasses and keep those plants from getting good access to sunlight. By cleaning the water, these isopods help the seagrasses and so could be considered one of the estuary’s good guys -- Levinson, take note.

Duffy compares isopods to another group of misunderstood invertebrates, insects. “We don’t like mosquitoes, but we like butterflies,” he says. “It’s a little bit similar with isopods. Some of them are really nasty, and some of them are our friends.”

The nasty ones fall under Jeffrey Shields’s expertise. Shields, also at VIMS, studies parasitic isopods. He focuses on those that live off of other crustaceans, from crabs to shrimp, often by growing under the gills of their larger hosts. But, as Levinson shows in The Bay, some isopods do target fish. The director has said that he was inspired by the case of Cymathoa exigua, an isopod that can grow up to an inch long. They’re frequently called “tongue-replacers.” That’s because, once inside the mouths of their fish hosts, they destroy the hosts’ tongues, then take the place of those muscles. Miraculously, these fish still seem to be able to eat even with their horrifying new appendages. But don’t fear just yet. C. exigua largely keeps to the waters off the Gulf of California.

The Chesapeake’s parasitic isopods, on the other hand, eschew tongues, Shields says. Two species, in particular, can be found locally clinging to the gills of striped bass, menhaden, and a few other fish species. Those ride-along isopods are Lironeca ovalis and Olencira praegustator. (Oddly enough, both Lironeca and Olencira are anagrams for “Caroline.” That was the tradition of William Elford Leach, a zoologist who lived in pre-Victorian England and named several groups of isopods. While rumors have been spun about who Caroline was, no one knows for sure). These two animals don’t seem to kill their hosts outright, but they can effectively neuter them, Shields notes. Infested fish divert so much of their resources to fighting off the parasites that they’re sometimes left with too little energy to reproduce.

Shields, for his part, isn’t grossed out by parasites like these. Parasites in the biological world are “largely ignored or thought of as ugly, icky things,” he says. “But fully 50 percent or more of the animals on the planet are parasites, so they can’t be avoided.” And, he says, by studying how other animals fight off their parasites, we can learn a lot about the human immune system.

In the end, how bad isopods really are may depend on whom you ask. If you talk to a crab or a rockfish, the little critters may be villains, indeed. But humans don’t have much to fear from them. Killer sharks, on the other hand, are a different story.