Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Why Do We Care About Stormwater?

You may have noticed that Maryland is a watery place. Between the Atlantic ocean, the Chesapeake Bay, several large rivers, and fairly frequent rain, it is hard to avoid the water in Maryland. As climate change shifts precipitation patterns toward more extreme rain events, flooding has started to literally fall from the sky. You no longer need to be within a river’s floodplain or along a coastline to experience flooding.

This is because rainfall can cause pluvial flooding, which is a scientific way of saying flooding caused by heavy rainfall that is not related to a body of water overflowing. To protect us from pluvial flooding, we generally depend on stormwater infrastructure—all the solutions we have created to move and contain rainwater away from homes, roads, and businesses. These can take the form of ponds, pipes, or even constructed wetlands.

Unfortunately, a lot of Maryland’s stormwater infrastructure was created when the state was much less developed than it is today. Areas that were once mostly woods and farmland are now mostly asphalt and steel. As a result, water cannot slowly sink into the ground and flow into rivers as it would have before cities and towns were built. Many of our pipes, ponds, and other structures are no longer large or well-maintained enough to do the job they were made to do—to move and hold water that quickly runs off of hard, impermeable surfaces. This can cause both flooding and increase the amount of pollutants that make their way into larger bodies of water like the Chesapeake Bay.

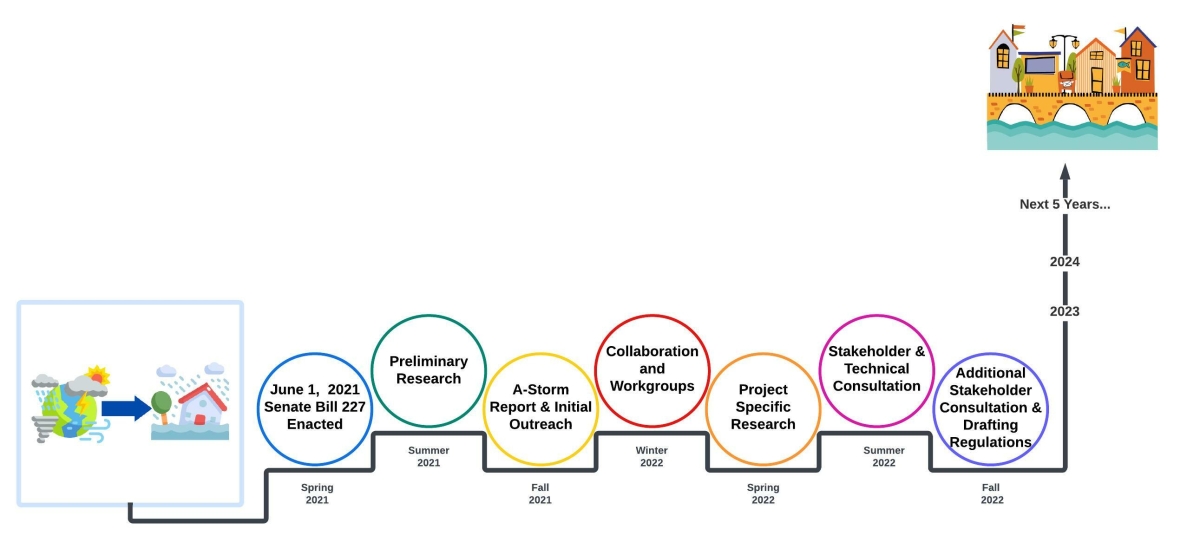

Changes in Stormwater Laws and Regulations

Damaging flooding events are already happening throughout the state, creating urgency around stormwater management. To help address these problems, the Maryland General Assembly passed Senate Bill 227 in June 2021. This bill focused on advancing stormwater resiliency in Maryland and mandated that the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) develop plans to evaluate current flood risks and change how it regulates stormwater to improve flood management. MDE is addressing this in a variety of ways, including:

- Understanding current rainfall data

- Investigating flooding in areas where water naturally flows, regardless of political boundaries

- Updating regulations and permitting practices to reflect this improved understanding

Bringing Together Science and Policy

Flood and stormwater resilience will make our communities safer and more adaptable to environmental change, but MDE’s Advancing Stormwater Resiliency in Maryland (A-StoRM) initiative requires extensive research, data collection, regulatory changes, and collaboration. That’s where my fellowship projects come in. MDE needs creative, efficient methods to collect data on local flood and stormwater management practices, regulations, and community needs.

Working with MDE’s stormwater and flood teams, I developed flood management interviews and stormwater surveys, which we are actively conducting in all of Maryland’s municipalities. We are collecting quantitative and qualitative data on stormwater management practices, collaboration challenges, and the availability of data for watershed studies and flood-prone areas. Eventually, this information will be used to gauge if communities with proactive stormwater and flood management programs are actually seeing fewer flooding events related to rainfall. In other words, are local stormwater management programs reducing flooding? And if not, how can we update regulations to help them work better?

This complex problem extends beyond the work of my fellowship and will continue to be a major project for MDE in the decades to come. Part of solving such challenges includes hearing the public’s perspective. If you want to learn more about A-StoRM, including opportunities for education and for public comments on regulations, you can follow our work on the A-StoRM Hub website. Bringing together the best available science with policy change is challenging, but MDE is actively working with other state agencies, academia, private and nonprofit partners, and the public to make the vision of a flood-resilient Maryland a reality.

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog