Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Lessons in Supporting the Bay’s Next Seven Generations

Retracing our steps from the Chesapeake’s Indigenous, colonial, and industrial past to learn how (and how not) to preserve the way forward.

The next generation of environmentalists is an interdisciplinary coalition of ecologists, biologists, geologists, hydrologists, engineers, and designers of the built environment, all committed to the protection and preservation of natural resources. Together, they combat the hard lessons of natural resource exhaustion.

As an emerging researcher working at the intersection of ecological and human health, I consider myself a member of this next generation. I am currently a Sea Grant Research Fellow with the Morgan State University Patuxent Environmental Aquatic Research Lab (PEARL). I assist the Baltimore BLUE-CORE (BLUEspace COllaborative REsearch for Urban Coastal Access and Climate Resilience in South Baltimore) team to improve South Baltimore’s access to blue and green spaces in their community. This research team gathers community insights about perceptions, preferences, and visions. South Baltimore residents are aware that the Chesapeake Bay is a resource and have opinions on the matter. But their limited access hampers their ability to create positive experiences that teach future generations to protect and preserve the Bay.

My background using landscape architecture to transform vacant lots into therapeutic landscapes in underserved neighborhoods across Baltimore City has given me perspective into the wide gap between urban communities and the benefits bestowed by access to nature. A city with parks does not necessarily mean there is one nearby. A vacant lot, though green, does not provide the same experience as a park with amenities like trees and gardens. Likewise, a community with a waterfront does not necessarily mean residents can walk right up to the water’s edge. In the case of South Baltimore, the barriers outnumber the beaches, and the bridges don’t have pedestrian paths that lead to the quiet coves. The roaring engines of tractor trailers and the churn of cargo trains drown out the soothing sounds of waves and the cooling breeze from the Chesapeake Bay. The South Baltimore waterfront is a perfect example of how people become disconnected from their environment.

The ever-expanding and rapid industrialization of the Bay has contributed to the decline of this once robust ecosystem. As we think ahead to the future of the Bay, our region’s history teaches valuable lessons in preservation. The history of Baltimore’s waterfront cannot be told without explaining the impacts of colonial settlement and urbanization.

Colonial History

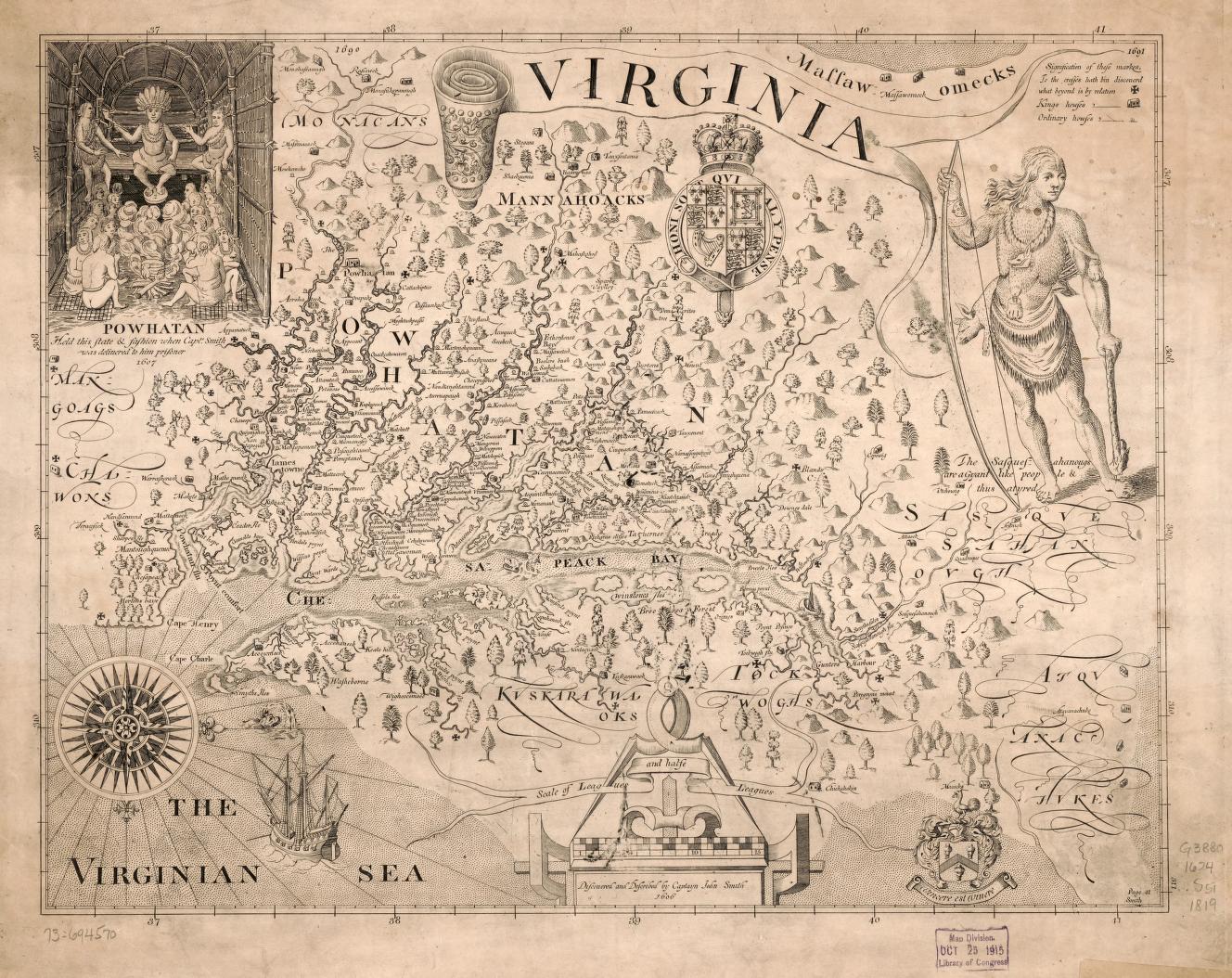

Depending on one’s arc of history, the story of Baltimore’s waterfront could start with Native Americans traversing the shores of the vast Patapsco River, or it could start in 1608 when the English Captain John Smith sailed the territory, surveying the Chesapeake Bay landscape. The Indigenous peoples of the area and European colonists had different intentions for the waterfront.

Native Americans in the Chesapeake Bay practiced a nomadic lifestyle. Some traditions valued the conservation of resources for the next seven generations. Through sacred and sensitive interactions with nature, reverence, restraint, and responsibility was achieved. Native Americans had occupied the area for tens of thousands of years and were able to maintain its health and wealth of resources. European settlers did not follow these same principles.

According to the mandate from England’s monarchy, the goal of Smith’s voyage was to map and claim land, find gold and other treasures, trade with the native peoples, and discover passage to the Pacific Ocean. Smith’s accounts of abundance from the bottom of the seas to the tops of the forested mountains sparked an explosion of colonial exploration and natural resource exploitation in the Chesapeake that is still occurring to this day. Smith described firsthand the heaps of oysters rising from the Bay, so common that they were a navigation hazard for ships. In addition to providing a source of food for people and wildlife, oysters are natural filters and contribute to the clarity and health of Bay waters. Since Smith’s time, the oyster population has declined to record lows, and water quality has suffered.

Industrial History

Nearly 100 years after John Smith’s journey, the Port of Baltimore was established in 1706. Contact with the Patuxent and Piscataway people, located south of Baltimore, led to an exchange of information about culture and crops. Soon after, the tobacco plant became the top trading commodity for the English colonists at the Port of Baltimore. Traditionally, tobacco was carefully prepared by hand and used in prayer ceremonies for the purpose of spiritual and medicinal healing. The sacred plant’s popularity with Europeans cast it as a lucrative agricultural crop. The lives and labor of humans became another commodity for European traders, starting with the local Indigenous community and then drastically scaling up to center around Africans.

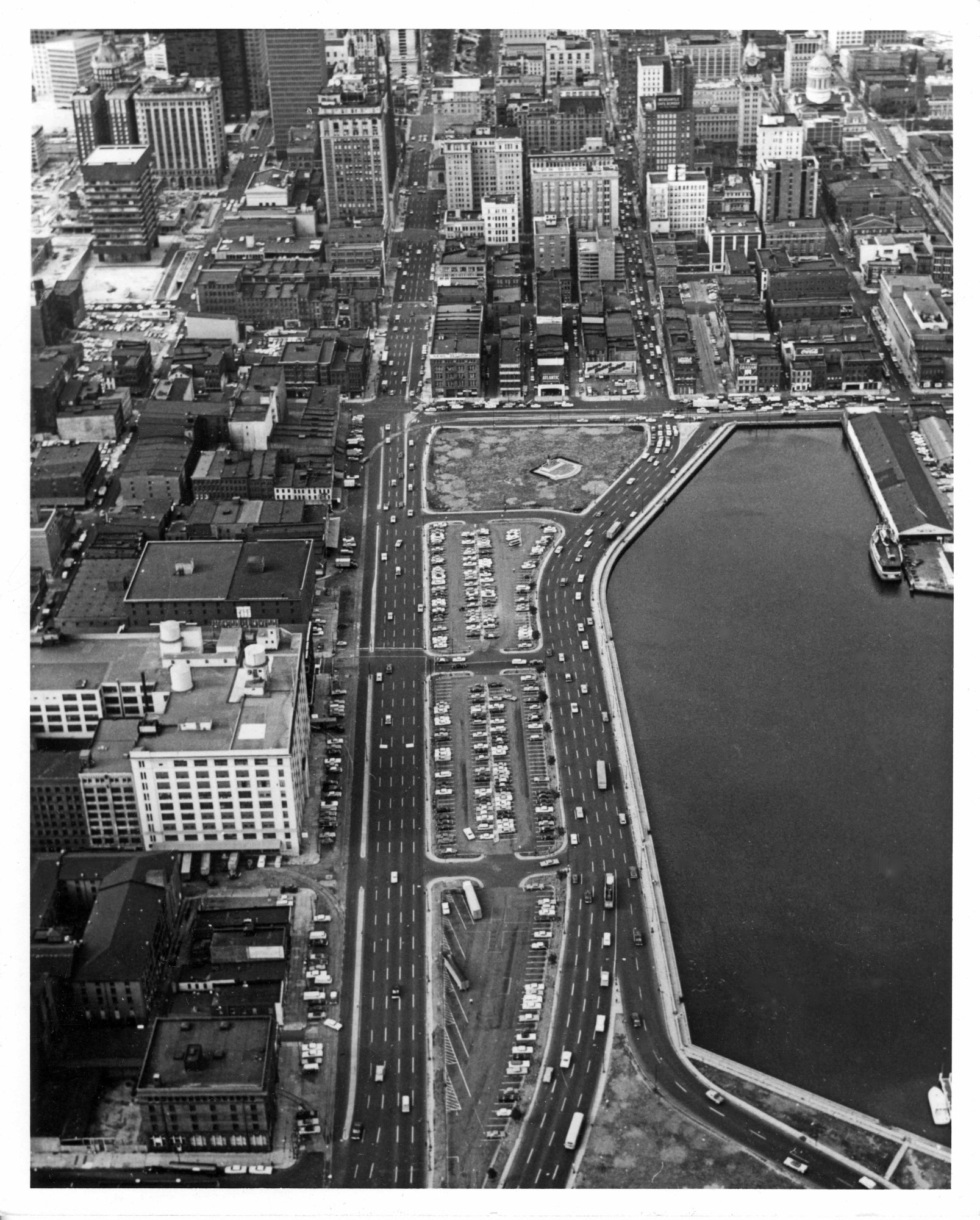

Within the next century, the Port of Baltimore grew in popularity. Vessels visited the port from as far away as China. With the introduction of the railroad, trade expanded to include Europe and South America. By the turn of the 20th century, Baltimore became an industrial powerhouse and a convenient producer during the World Wars. Eager to operate near a main transportation hub, war industries flocked to the area, and with the steel mills and shipbuilding came toxic pollutants, such as arsenic, sulfuric acid, lead, and mercury. After the wars, many soldiers returned to Baltimore to work for the manufacturers who pivoted their war technology into consumer product markets. Synthetic material companies producing paints and plastics bought up coastal edges and used the adjacent Bay as their waste facility.

The 1950s to 1970s marked the construction period of highways, super bridges, and submerged tunnels, which allowed tractor trailers and millions of automobile commuters to traverse the Baltimore Harbor and Chesapeake waterways. Well-paying factory jobs attracted workers. These workers needed undeveloped land—the forests and wetlands buffering the Bay—for housing. Harbors and ports across the Chesapeake bustled with commercial activity. Beneath the surface, however, agricultural and seafood communities struggled. A search for scientific innovations that would improve the quality of water, air, and soil was beginning.

“Save the Bay” has long been a rallying cry for champions of the Chesapeake Bay. But what does “save” mean? For the last 50 years, the environmental movement has mobilized thousands of people through advocacy and education. Those efforts have accelerated the pace toward a healthier Bay. But despite progressive action and protections dating back to the pivotal Clean Water Act of 1972, the Chesapeake Bay region continues to urbanize at a rate that threatens conservation and preservation. Urban centers feel the negative impacts more acutely and require adaptive management. Particularly in urban landscapes and waterfronts, there is a need for long-term resiliency planning and to tackle urgent preservation and restoration projects.

To me, preservation is about getting ahead of the needs of the future; it represents the “pre-service” we do today in advance for those to come. Environmentalists must engage with history to understand how we got here, and we must impart these lessons upon the next generation.

Top left image: Key Bridge under construction, 1920. Credit: public domain.

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog