Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Lessons from Hawai‘i and California on the Future of BlueTech

Some trips change how you see a place; others change how you see the world. Our fact-finding trip to the Aloha State did both. While I have been lucky enough to visit Hawai‘i before, I have never seen it through a lens quite like this. I was invited to join a congressional delegation to see firsthand how ocean-based innovation and biotechnology translate into science policy challenges and opportunities—from sustainable food systems to climate resilience and economic growth. Our goal was to understand how science, culture, and climate adaptation intersect to shape ocean policy. Hawai‘i revealed that story, one experience at a time.

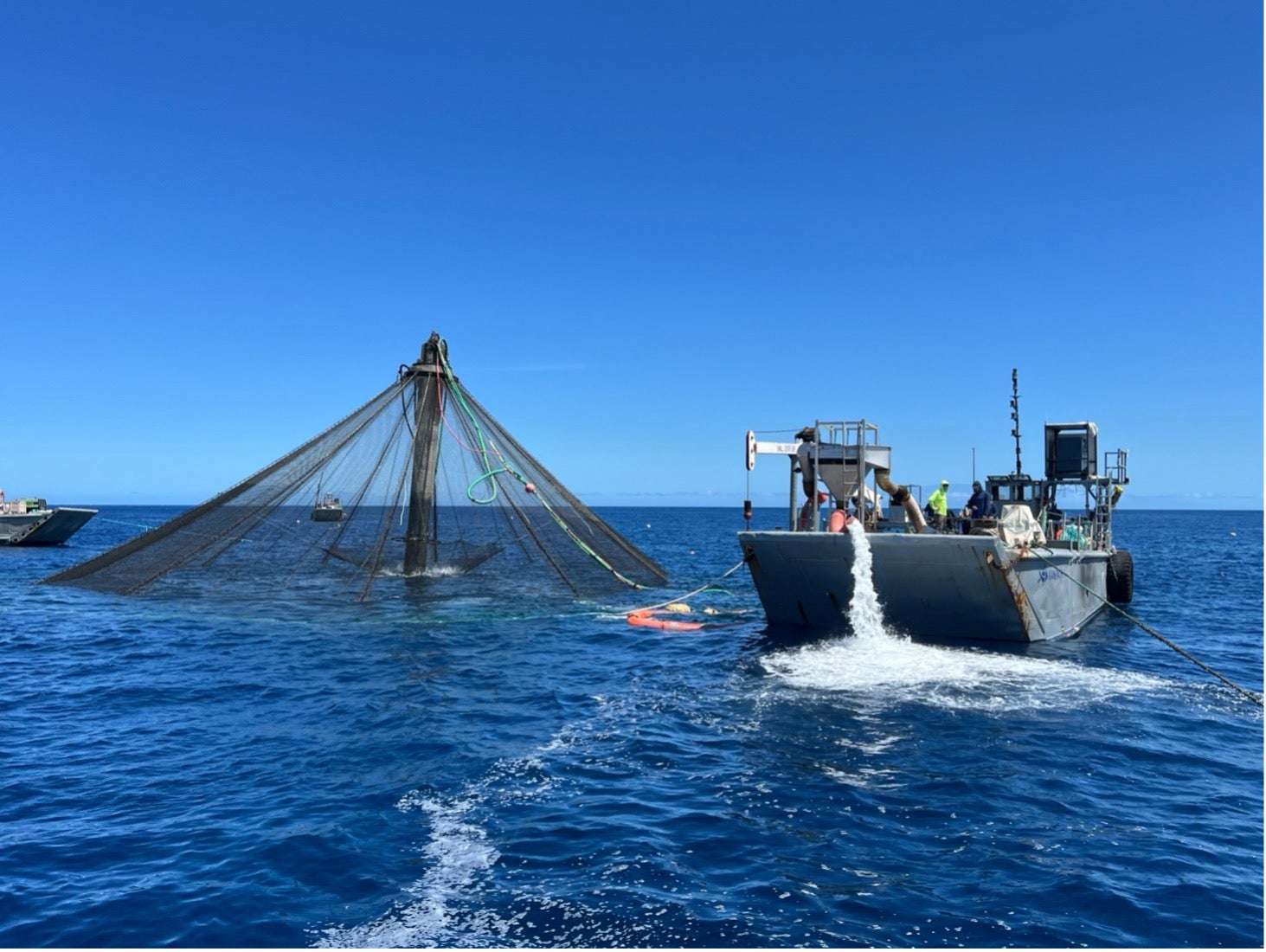

On the Big Island, our first stop was Blue Ocean Mariculture, home to one of the only commercially farmed open-ocean finfish operations in the United States, raising Hawaiian Kanpachi. Touring the hatchery made it clear how much precision and care go into producing healthy, sustainable seafood. Every detail matters: water quality, oxygen, temperature, feed, and even the engineering behind the offshore pens.

Meanwhile, the global trend toward farmed seafood is accelerating. As of 2022, aquaculture accounted for just over half of the world’s aquatic animal production by volume. At the same time, the US still imports roughly 70–85% of the seafood Americans eat. The gap between what we consume and what we produce is striking. It raises a bigger question: What would it take to responsibly and economically grow more seafood at home?

The next day, we headed offshore to visit the open-ocean pens where the Kanpachi are raised. As we moved farther from the Kona coast, the island faded into a thin line, and the Pacific Ocean stretched out in every direction. It felt like a reminder of how vast the ocean is, and how small we are within it.

After the tour, we stopped to snorkel near a reef not far from the fish farm. I expected coral and a few reef fish. Instead, the ocean surprised us. In the warm evening light, several manta rays appeared below us, gracefully circling even though this wasn’t their usual nighttime feeding hour. Floating above them, I felt humbled and grateful. Seeing these animals up close reminded me that, despite being tiny in comparison, humans still have enormous consequences. We carry the responsibility to protect the very systems that keep us alive.

Later in the week, at Kīholo Preserve, we visited traditional Hawaiian fishponds, or loko iʻa. Many of these fishponds were built between 1200 and 1600, using natural rock walls and tidal flows to raise fish in brackish water. They aren’t as old as some Asian aquaculture traditions, but they are beautifully adapted to Hawai‘i’s environment and culture. Their design shows that sustainable ocean food systems aren’t new. They’re rooted in deep local knowledge, careful engineering, and stewardship across generations.

In Honolulu, at NOAA’s Inouye Regional Center, discussions turned to US seafood production, climate pressures, and the need for innovation. Those conversations made me think back to my own scientific background in microalgae biotechnology and engineering strains to produce more lipids for biofuels and high-value products, such as antioxidants and pigments. It became clear that biotechnology is not separate from the blue economy, which focuses on the sustainable use of ocean resources to create economic value while protecting marine ecosystems. Rather, biotechnology is a key engine powering the blue economy’s growth.

Whether we’re talking about algae, fish, offshore sensors, or new biomaterials, the throughline is the same. Research, technology, investment, and collaboration are what turn big ideas from concept into real impact.

The second half of my journey took place during BlueTech Month in California. If Hawai‘i gave quiet clarity, California gave momentum.

In San Diego, leaders from ports, universities, startups, philanthropy, and government gathered to discuss the ocean, not just as a natural system but as a platform for innovation and jobs. Many discussions focused on clean shipping, ocean intelligence, autonomous vessels, community partnerships, and preparing a new workforce. The message was simple: If we want a sustainable ocean economy, we need long-term collaboration, steady funding, and science that moves from the lab to the water. It also takes policies that help scale what works, while ensuring communities share the benefits.

All of this felt even more important in the context of a growing world. As the global population increases, so does our demand for electricity, food, and resources. The ocean will play a major role in meeting these needs, but only if we approach it responsibly. Sustainability is not optional. It is the foundation of everything we hope to build.

One scene from the BlueTech trip tied it all together. The Norwegian tall ship Statsraad Lehmkuhl sailed into San Diego Bay and was greeted by a cannon salute. In that moment, history met the future. On land, people were discussing AI tools, deep-sea exploration, zero-emission shipping, and next-generation ocean technology. On the water, a vessel more than a century old reminded us that the ocean has always been central to human life. It also underscored that progress is most meaningful when it builds on what came before.

Across both coasts, the message was clear. Hawai‘i showed us why the ocean matters: its beauty, culture, and ecological importance. California showed us how we can build a sustainable future through innovation, policy, and teamwork. Together, they demonstrate the scale of the challenge and the opportunity.

I left this journey feeling humbled, inspired, and motivated. The ocean is massive and still largely undiscovered, but so is our potential to make a difference. We may be just a drop in the ocean, but our choices today create the ripples that will shape generations to come. We have the tools. We have the science. Now, we need the will and the follow-through to turn learning into action.

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog