Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

From the Lab Bench to Capitol Hill: A Scientist’s Journey Through Congress

You might think there are few parallels between the science conducted in a molecular biology lab and the work of lawmaking that happens on Capitol Hill. But one of the surprises of my time in Washington, DC, has been how it felt less like a career change and more like stepping into a new ecosystem with a completely different set of instruments. In the lab, my day was built around cultures, time points, and the quiet logic of experiments. On the Hill, the “equipment” is language, procedure, relationships, and a clock that never stops. One moment you’re thinking about metabolism and pathways, and the next you’re walking through the Capitol basement trying to remember whether a “pro forma session” means people are working or simply keeping the chamber officially open.

But the longer I’ve been here, the more I’ve realized something reassuring: Congress isn’t mysterious. It’s a system. It’s messy because it’s human, but it’s learnable. And once you understand the terminology, you can follow the flow of power, decisions, and priorities.

The first thing you learn is that everything revolves around time, specifically the congressional calendar. If something isn’t scheduled, it’s not moving. When Congress is in session, members are in Washington, DC, votes happen, committees meet, and decisions pile up fast. When Congress is in recess, it sounds like a break, but it’s closer to fieldwork. Members go back home, meet with local leaders, visit schools and facilities, and listen directly to the people they represent. As a scientist, that rhythm felt instantly familiar to me. A session is the time during which the experiment runs and results are recorded. Recess is where you collect observations from the real world and refine the question you’re trying to solve.

And those questions can start anywhere. Sometimes it’s a human health threat like PFAS, often called “forever chemicals,” because they persist in the environment and can be difficult to remove from water systems. Other times it’s an infrastructure challenge, such as flooding or aging water systems. And sometimes it’s an energy question, like how to scale sustainable biofuels and other renewable alternatives without compromising food systems or ecosystems. In science, we’re trained to begin with a problem statement and a hypothesis. In Congress, that hypothesis becomes: What policy change could move the needle? That’s the moment an idea starts turning into a concrete solution—and eventually, draft legislative language.

This is where behind-the-scenes experts matter more than most people realize. There’s the Congressional Research Service (CRS), which is basically the research engine for Congress. CRS is nonpartisan, fast, and built to answer the questions staff ask every day, such as: What does the law currently do? What has been tried before? What does the evidence say? What would this cost? What do different stakeholders argue, and where are the tradeoffs? If you’ve ever wished the internet came with a built-in peer review filter, CRS is the closest thing Congress has.

Then, there’s the Office of the Legislative Counsel, which turns policy ideas into actual legal language. If an office has a concept, Legislative Counsel is the team that helps translate it into something that can be inserted into the US Code without collapsing under its own ambiguity. It’s not just writing. It’s precision drafting, because every word can change how an agency implements something, how courts interpret it, and whether it creates clarity or confusion.

Over time, I learned that the real work of Congress often doesn’t happen where people expect. Movies make it look like everything happens during dramatic speeches in the chamber. In reality, most shaping happens in committees, and the process has its own vocabulary. A briefing is often a learning session. It’s closer to a seminar, where staff and members hear from experts, agencies, advocates, and researchers to understand the issue. A hearing is more formal. Witnesses testify on the record, members ask questions, and it becomes part of the official public process. And then there’s markup, which is where the actual text gets edited.

Markup is the policy equivalent of opening a shared document and watching a sentence get rewritten 20 times, except every edit has political consequences, and every revision can create winners and losers. In markup, members offer amendments, which are proposed changes to a bill’s text, and they debate and vote on which changes stay. That’s also where you hear a word that sounds almost academic: germane. Germane means relevant. An amendment is supposed to relate to what’s being debated, not wander off into an unrelated topic. The question, “Is it germane?” becomes one of the most common gatekeepers of what can and cannot be added in the moment.

If a bill survives the committee process, the next big stage is the floor, which sounds literal because it is, but it also describes a phase. “On the floor” means the full House of Representatives or the full Senate is debating and voting, not just a committee. Floor time is limited and strategic, and that’s why you can hear about important ideas that seem popular but still don’t move. It’s not always about merit. Sometimes, it’s simply about time, priorities, and the reality that Congress is juggling many issues at once. Also, Congress is bicameral, meaning it has two chambers, the House and the Senate. Both must pass the same bill for it to reach the president. That alone creates friction, negotiation, and delay, even when everyone agrees on the goal. Then, add politics, and you start to understand why people say progress can be slow.

Something else that took me a moment to internalize is that Congress produces different things. A bill proposes a change in law. If it passes both chambers and is signed, it becomes law. A resolution can do several different jobs. Some resolutions express a sentiment, like recognizing an event or honoring someone. Others set rules for debate or govern internal operations. Some resolutions can even become law, depending on their form. And then there are reports, especially committee reports, which are official documents that explain what a bill does and why it matters. Reports can later become part of how a bill is understood, because they often capture intent and context, just as the introduction and discussion of a scientific paper frame the meaning of the results.

Funding has its own language too. Once you learn it, you start hearing it everywhere. Authorization is like designing the program, setting the boundaries, and giving it a legal home. Appropriations is the money. In plain English, authorization says, “We should do this, and here’s how.” Appropriations says, “Here’s what we’re actually paying for.” You can authorize something brilliantly and still not fund it. You can also fund something temporarily without building a lasting structure. And sometimes you’ll hear people talk about community projects, which are often local investments tied to real needs, like infrastructure upgrades, resilience projects, ports, or water systems. These are tangible outcomes that constituents can see, and they also come with rules, transparency requirements, and debates about how federal dollars should be directed.

The most grounding moments, though, aren’t always the big procedural ones. They’re the constituent meetings, when the policy questions stop being abstract. Constituents are the people who live in a member’s district or state, and their concerns are often immediate and practical. A mayor trying to protect neighborhoods from flooding. A utility manager worrying about cybersecurity threats. Researchers asking how to scale a technology beyond the pilot stage. Small business owners trying to survive the cost of energy. Families dealing with contaminated water. If science gives you tools to understand problems, constituent meetings remind you why the problems matter.

And then there’s the public-facing side of the Hill, which is its own kind of communication science. Press conferences are part information, part narrative, part strategy. I remember organizing one press conference themed around demands for cheaper, cleaner energy for everyone, and realizing how quickly a message can shape what people pay attention to. In research, we publish papers and hope the right people read them. In politics, attention is a form of power. Messaging can speed up momentum, signal priorities, and pressure institutions to act. It can also oversimplify. Learning to communicate without flattening the truth is one of the hardest skills in both worlds.

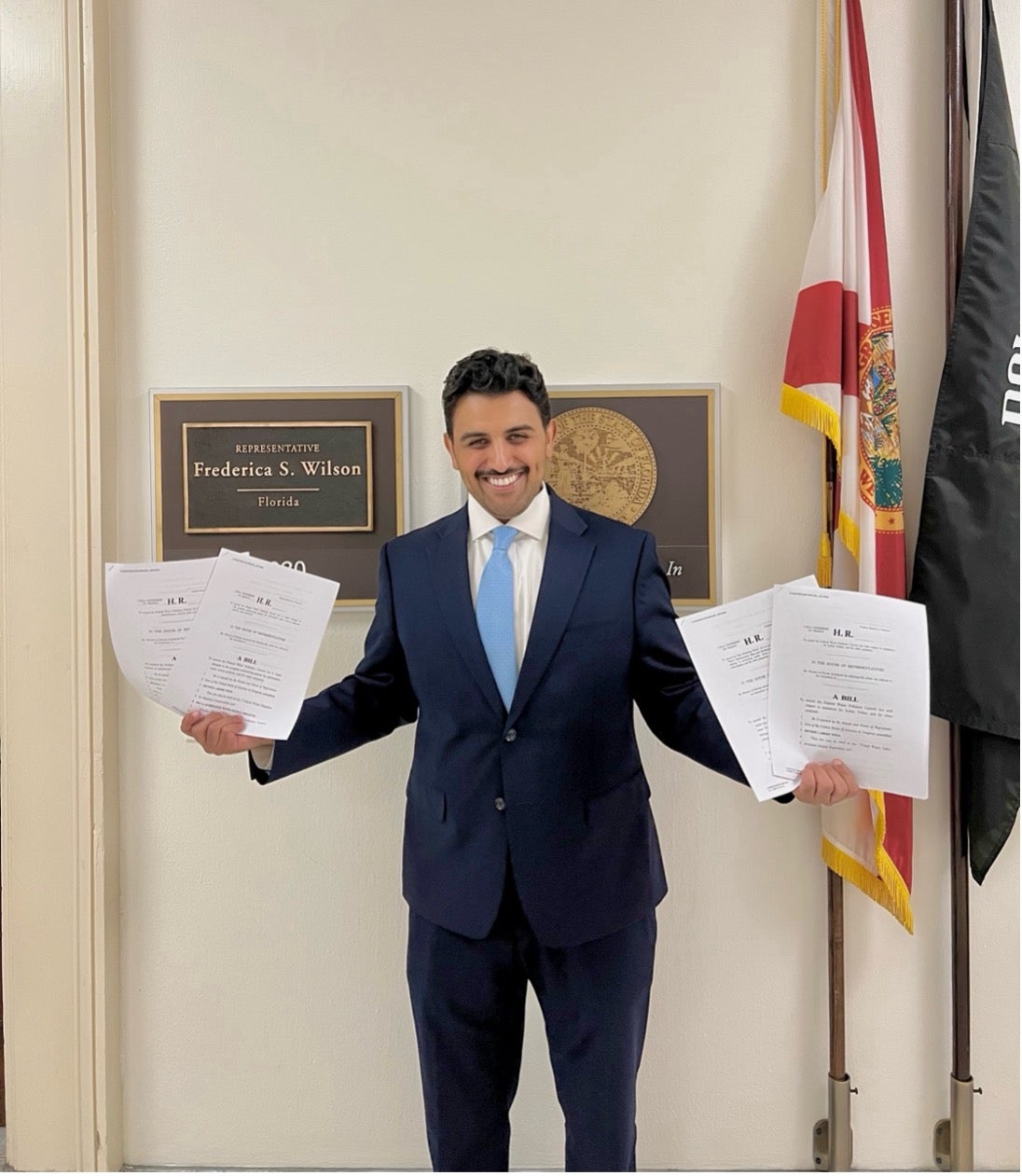

One of the most memorable moments of my journey in Congress came right in the middle of all that: I helped manage the introduction of four bills, including a water cybersecurity bill that we worked hard to make bipartisan by meeting with offices across the aisle and securing Democrat and Republican cosponsors.

That line sounds dramatic until you live what introduction requires. It’s not just dropping a document in a box. It’s aligning language, confirming jurisdiction, working through drafting with the Office of the Legislative Counsel, checking facts with the Congressional Research Service, coordinating support, preparing summaries, anticipating questions, and making sure what you’re putting forward can survive both scrutiny and implementation. It felt surprisingly similar to preparing a scientific paper for publication, except instead of reviewer comments, you’re navigating procedure, politics, and timing, all while remembering that the outcome can affect real communities.

What I’ve come to appreciate most is that Congress is slow in the same way science is slow: not because nothing is happening, but because accuracy, process, and buy-in matter. There’s a reason bipartisan work, meaning support from both parties, is often the difference between something that passes once and something that lasts. Durable policy usually needs broad support, not just a strong argument. And even then, the system is designed to force negotiation. It can be frustrating. It can also prevent whiplash.

I used to think coming to Capitol Hill might mean leaving science behind. Instead, it’s made me see science differently. The habits we learn in the lab—defining a question, checking assumptions, reading evidence carefully, documenting steps, revising when new information appears—are exactly the habits the public deserves in policymaking. The tools are different here, but the mindset transfers. That’s why I genuinely hope more scientists step into policy and science diplomacy, not to leave the lab, but to make sure evidence travels farther and builds trust across communities and countries.

We need more people who can efficiently translate data into decisions and turn collaboration into real-world outcomes. And once you learn the Hill’s language—hearing versus briefing versus markup, bill versus resolution, authorization versus appropriations, floor action, germane amendments, bicameral process—you realize something unexpectedly hopeful: this system isn’t magic. It’s mechanics. And mechanics can be understood, improved, and used to translate knowledge into action.

Top left photo: Abdulmajid Alrefaie on the Speaker’s Balcony at the US Capitol, overlooking the National Mall in Washington, DC. Photo: Abdulmajid Alrefaie

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog