Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

For the Farmer in Nebraska and the Lonely Buoy in the Middle of the Ocean

When I started my Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship, I found myself fixated on a single, somewhat specific question: How can we convince a farmer in Nebraska to care about a buoy floating in the middle of the Pacific Ocean?

On the surface, they seem worlds apart. One is standing on the edge of a cornfield in the Midwest, thinking about planting dates and fertilizer. The other is a piece of hardware thousands of miles away, beaten by freezing waves and completely alone in the middle of the ocean. It feels like a riddle, but as I dug into my research this year, I realized the answer wasn't a stretch at all. In fact, that farmer’s livelihood often depends entirely on that buoy.

One concept that really stuck with me this year is the “value chain.” It sounds like boring business jargon, but in the world of weather, it basically asks: How do we get from a single observation in the middle of the ocean to the application on your phone? We often think weather is local. We look out the window to see what’s happening here. But the atmosphere is a giant, chaotic fluid that wraps around the globe. The storm system that might flood a basement in Texas or water a field in Nebraska often starts its life days earlier, as a swirl of moisture and pressure over the ocean.

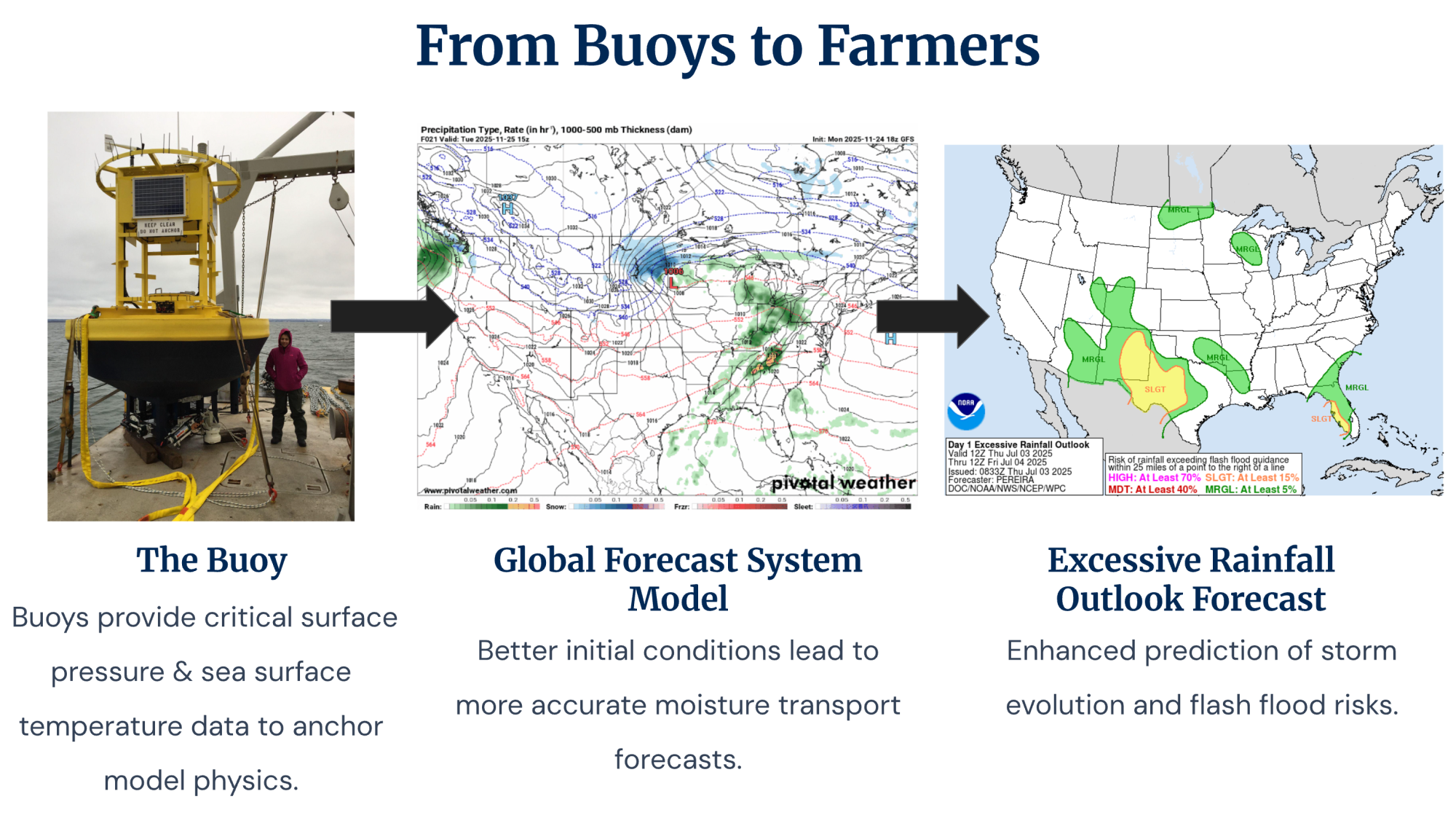

This is where the buoy comes in. My project this year was to look at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) “Precipitation Prediction Grand Challenge." It’s a fancy name for a very urgent goal: figuring out how to stop getting surprised by extreme floods and droughts. To do that, I looked at the machinery behind our weather forecasts, specifically the Global Forecast System (GFS).

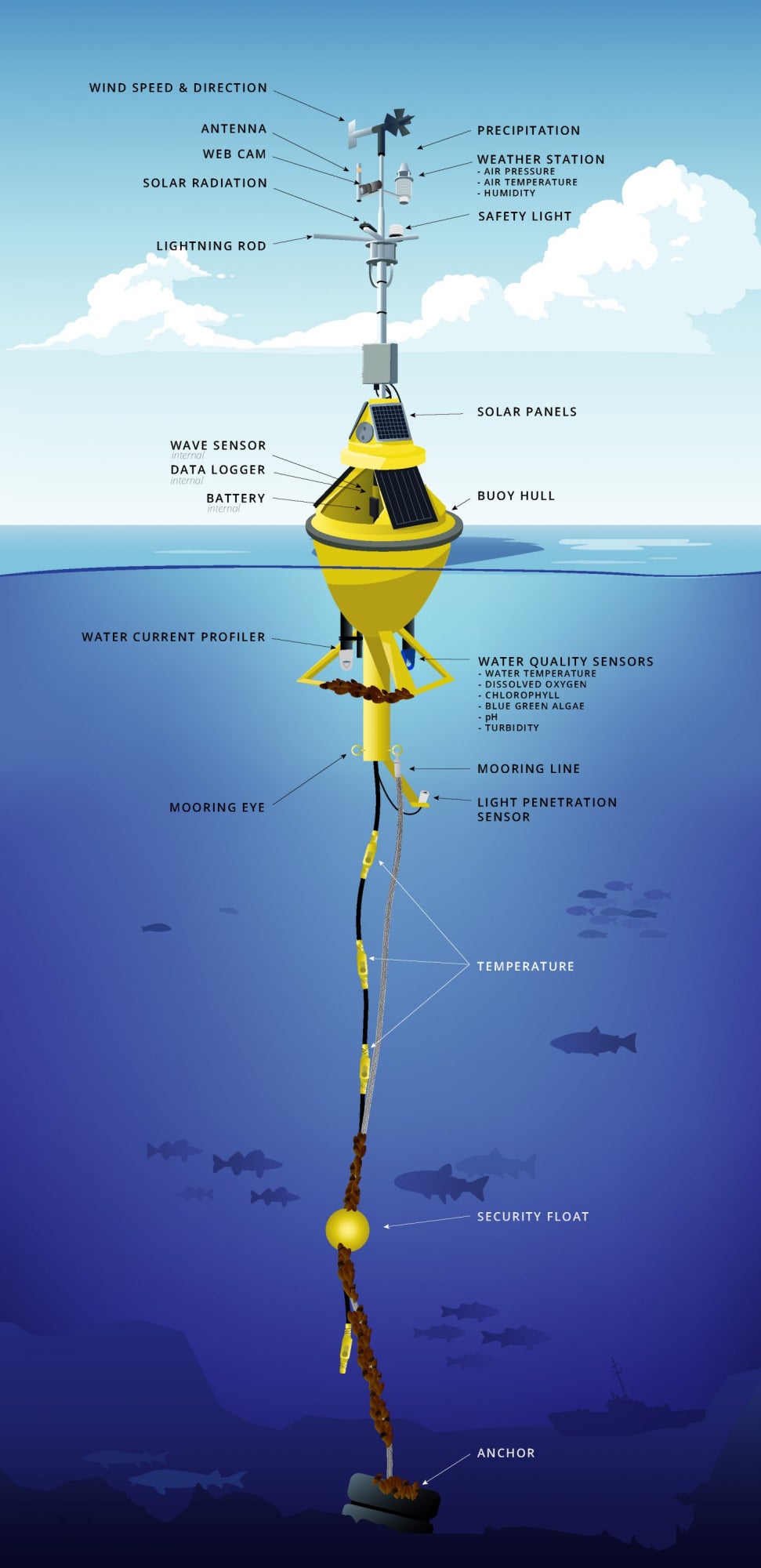

You can think of the Global Forecast System as the "engine" that powers weather predictions worldwide. I found that this engine is hungry. It needs massive amounts of data to run correctly. If you feed it bad ingredients (poor data), you bake a bad cake (a bad forecast). My research found that one of the most critical "ingredients" for the GFS comes from ocean buoys. These floating sentinels measure things satellites sometimes miss—like the exact air pressure at the water’s surface or the heat rising off waves.

The connection is surprisingly direct: The buoy in the ocean measures a drop in pressure or a spike in wind speed. That data is beamed to NOAA supercomputers, helping to correct the "initial conditions" of the GFS model. That model output then feeds into the "Excessive Rainfall Outlook," the map that tells emergency managers and farmers if extreme rain is coming. If that buoy isn't there, or if it’s broken, the model guesses. And when the model guesses about conditions in the Pacific, it might get the forecast wrong for the Great Plains three days later.

This isn’t just about data points or computer servers; it’s about people. The ultimate goal of this "value chain" is to promote social and economic safety. When we talk about improving data, we are really talking about buying time. For a family in a flood zone, better data means an evacuation warning arrives hours earlier, giving them time to secure their home and get their children to safety. For the farmer in Nebraska, accurate data means knowing exactly when to harvest before a storm hits, securing the food supply and their family's income. We often focus on technology, but the real impact is human. It is the difference between a community that is caught off guard and a community that is prepared.

Coming into this fellowship, I was a biogeochemist with a very specific set of loves: baking, searching for antiques, tending to my chickens, and getting my hands dirty studying nitrogen and mud. I didn't spend my days thinking about weather models or the hardware floating in the deep ocean.

However, this experience has given me a profound new perspective. I have gone from focusing on the mud beneath my feet to having a deep appreciation for the vast, often invisible network of ocean observing systems that watch over us. I now understand that those lonely buoys are not just distant scientific instruments. They are the “guardians” that keep us safe, ensuring that a family on the coast has time to prepare for a storm, and that the farmer in Nebraska is well equipped to bring in a successful harvest.

See all posts to the Fellowship Experiences blog