Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

SET Up for the Future

Phillips Creek Marsh lies on the final seaside stretch of the Delmarva Peninsula in Virginia. It is a swath of wetland grasses with patches of reeds and warped remnants of a boardwalk. Pines fringe the uplands, and a flock of seabirds socialize on a distant mudflat to the southeast. The sky on a Thursday in mid-May was an overcast milky blue. It certainly beat my usual office window view of a parking lot. That morning, I took my first squishy steps into the marsh so I could help with the Virginia Coast Reserve Long Term Ecological Research (VCR LTER) annual Surface Elevation Table (SET) measurements.

I’m one of a dozen helpers who have gathered around wetland microbiologists, Linda Blum (University of Virginia) and Bob Christian (East Carolina University). They have been consistently monitoring this marsh for the past 21 years. Very few, if any, sites can beat this monitoring record in the United States. (It may be one of the longest records in the world). After these two decades, Blum is ready to delicately pass the baton to the next generation of wetland scientists, Keryn Gedan, a wetland ecologist at George Washington University, and Cora Johnston, the new site director for Anheuser Busch Coastal Research Center.

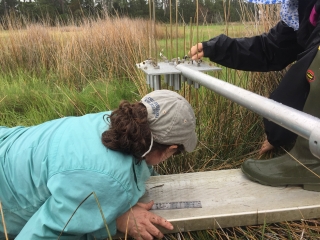

We tromp through the grass and mud until we are told to stop and come no further. Each surface elevation table is framed with wooden posts and planks. In the center is a benchmark, a pipe that has been driven deep into the ground. This benchmark should not move. However, the marsh around it might grow taller or sink down. A SET precisely measures the elevation of the marsh in millimeters.

We learn about marsh elevation when we measure the SET pin height. The SET is a metal arm that attaches to the benchmark; the arm holds nine pins in place. The benchmark and arm are locked into the same place every time. Then, researchers lower pins to the marsh’s surface and measure the height above the arm. The higher the number over time, the more the marsh has gained in elevation.

Over many years, we may observe centimeters’ worth of change. Marshes gain height through new sediment deposits or added organic matter such as plant roots. Marshes lose height through erosion or soil compaction. If a marsh is gaining, it may be able to withstand sea level rise. If a marsh is sinking, sea level rise will cause it to be underwater longer and the land may transition into mudflats. Blum’s and Christian’s work, which is duplicated throughout the Sentinel Site Cooperatives, gives us insight into whether marshes will survive with changing conditions.

While the concept is simple enough, performing the measurement requires precision, since millimeters make all the difference. You can’t get near the SET; otherwise we might be measuring your footprints. The scientists stand, sit, or lay on planks in order to do SET measurements, but not touch the ground. Putting the pin on the surface of the marsh is not as easy as it sounds. Sometimes, it’s like navigating through pea soup. Sometimes, sharp reeds surround your face. Two people could measure the same spot and come up with a different number, so it’s important that the same person measure the SET every time. The helpers are there to note the SET arm’s compass orientation, record the measurements, and carry planks to rest on between the sites.

My team has 11 SET sites to measure. It takes us between four and five hours with birds cawing overhead and flies buzzing much closer. I wonder with every step I take if this time I will fall in the mud (I don’t! Whoohoo!). Blum and Christian traverse the marsh visiting and helping the two teams. You can tell they know the marsh like the back of their hand and have seen it grow in and shift in a way imperceptible to most people.

I consider myself lucky to learn this story for at least one day in the marsh. My hope is this new generation will continue to learn and watch Phillips Creek for another twenty years and then they’ll past the baton too.

Photo, top left: Keryn Gedan lowers the pins to the marsh’s surface. Credit: Taryn Sudol

See all posts from the On the Bay blog