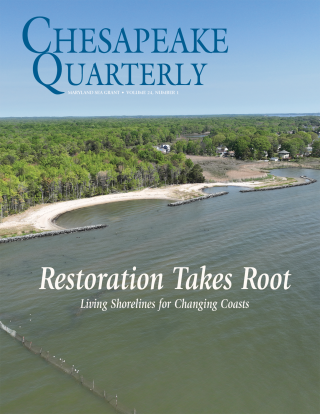

Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Lightning Safety

The threat of lightning is easy to ignore on an overcast summer day, but it can kill unprepared boaters without warning. Carrying as much as 100 million volts, it can smash a hole through a hull, explode a mast, and electrocute several people in a single flash. The thunderstorms of the Chesapeake Bay pose a lightning threat every boater should know about.

What is Lightning?

Lightning is nature’s way of equalizing conflicting charges in the atmosphere. These charged form most often when cool and warm air masses collide.

During a storm, negative charges build up in the base of clouds. As they pass over the earth, they create a positive charge in the normally negatively charged terrain. The positive charge works its way up tall objects, pulled along by the negatively charged clouds. As the positive charge forms an arc, lightning strikes.

How Dangerous is Lightning?

In the United States, lightning consistently kills more than 100 people per year. That’s more than other natural disasters, such as hurricanes, floods, or tornadoes. Risks are especially high for those who spend time outdoors, including farmers, fishermen, or boaters.

Water and lightning are a natural combination. Water conducts electricity very well, and when you add in the high profile of a boat surrounded by open water, there is an increased danger of getting electrocuted during a storm.

Take steps to stay safe. Here are tips from Maryland Sea Grant and University of Maryland Extension. Click on each heading to learn more.

What Can You Do?

To protect yourself in a boat, the important thing is to give lightning a ground. Boats made of steel, such as naval vessels, have an automatic ground in their metal hulls; but most small boats, usually constructed of fiberglass or wood, prevent the lightning easy access to the water and pose a grounding problem. Small boats may also lack tall objects that could deflect lightning. And even boats that do have tall spars -- like sailboats -- can run into problems if their spars are not properly grounded. The following grounding system will minimize the risk of lightning damage:

- On a sailboat, make a lightning rod using a piece of aluminum that sticks about 1 foot (30.48 centimeters) above the mast. Sharpen the rod to reduce resistance at the top. A radio antenna can also conduct electricity but may lead lightning to the radio and may well vaporize it during a strike.

- From the rod, lead a wire down a wooden mast; an aluminum mast can serve as its own conductor as long as a wire is led from its base to direct the charge to the ground. (A wooden mast with a metal sail track can be grounded as though it were a metal mast.) The Coast Guard finds a #8 wire adequate, though a larger gauge, say #4, further reduces heat and resistance.

- Attach this wire to a copper ground plate mounted on the hull beneath the waterline or dangled underwater. A square foot of copper flashing, easily obtained at many hardware stores, will make an adequate ground plate. If you decide to attach a permanent ground, use large stainless steel bolts, say 1/2 inch, to prevent their cracking under large electrical discharge. To increase safety, some recommend all stays be grounded to the plate.

- On a motorboat that has no high spar, use a metal radio antenna (not a fiberglass one), attaching a wire to a ground plate, as described above. If there is a loading coil on the antenna, use a shunt of 31-strand, 17-gauge, bare lightning grounding mesh to bypass it -- this will make the whole height of the antenna an effective ground. Quick-release clamps will allow an easy temporary attachment. (On a fiberglass antenna you can clamp the wire to a metal rod, letting that act as a lightning interceptor.) Use a "lightning arrestor" to protect your radio.

- When leading the wire to a ground, avoid sharp bends or turns. Any bend in the wire should have a radius of at least 60 degrees.

- One alternative calls for leading the grounding wire to a metal strip that runs down the bow or stern and maintains constant contact with the water. This offers the advantage of carrying the charge, at a gradual angle, safely away from the engine and the helm.

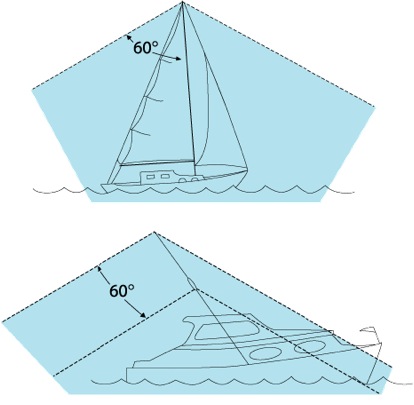

- Both the mast and the whip antenna will provide a "cone of protection" with a radius of approximately the same dimension as the rod's height. For most small boats, this will include the entire deck area. There may be, however, induced electrical surges created by the lightning, and for this reason large metal objects -- engines, for example - should be avoided during a storm. (Remember that an engine will have its own ground in the propeller and the shaft.) Induced electrical charges can cause arcing and electrical shocks strong enough to knock you unconscious, perhaps producing dangerous heart arrhythmias. A lightning strike can also magnetize a keel or other, metal fittings, rendering your compass useless.

First Aid for Lightning

After a shipboard lightning strike, check to see that everyone is all right -- it is, of course, perfectly safe to handle someone who has been hit by lightning. Check for burns, which should receive normal first aid treatment. (Don't put ointment on severe burns; cover them with clean cloth or plastic to keep out air.)

If someone has been knocked unconscious, act immediately: check for breathing and heartbeat.

If you feel a pulse, but no breathing, begin mouth-to-mouth resuscitation (a handkerchief over the mouth will help the squeamish). If there is no heartbeat, begin cardiopulmonary resuscitation, a technique every serious boater should know.

Precautions

Grounding your boat and unplugging radios and electrical equipment during a storm are good ideas, but the best precaution against lightning is avoidance. Especially in small craft, keep a weather eye out for the coppery haze and building cumulonimbus clouds that signal thunderstorms, heading ashore well ahead of the turbulence.

Remember that lightning can lash out for miles in front of a storm, and it can strike after a storm has seemingly passed. Remember, too, that, storms can bring high winds and waves, making a last-minute trip to shore a dangerous dash. The best maneuver of all is to think ahead.

Download a pdf of our brochure, Lightning: Grounding Your Boat, containing this information.

Photograph of lightning, NOAA