Knauss legislative fellowships in Congress help build careers — and they're fun and educational. See our video and fact sheet for details.

Photo Essay: An Island for Dredged Sediment Becomes a State Park for People

Hart-Miller Island started to take its current shape more than 30 years ago as a solution to a problem: where to store tons of sediment dredged from ship channels each year to allow cargo to reach the Port of Baltimore.

The solution: deposit the sediment atop the remains of two natural islands, Hart and Miller, at the mouth of the Back River that waves had nearly washed away. The Maryland Port Administration turned the two islands into one by building a perimeter of dikes that encompassed much of the islands' original footprints, a strategy that created a huge storage bin capable of holding several decades of dredged-up sediment. This engineered island received its first loads of sediment in 1984 and its last in 2009, when the facility reached its capacity. During that span, this newly created island grew and grew.

Since the early 1980s, the island has attracted boaters who visited and enjoyed a 3,000-foot-long sandy beach constructed along the island’s western edge. But most of the artificial island’s 1,100 acres remained off limits – until now.

This month Maryland's Department of Natural Resources (DNR) is officially opening the 300-acre, southern part of Hart-Miller Island to the public for walking, biking, and other recreational opportunities. The island offers a public resource that has been rare in the upper Chesapeake Bay: an island, beach, and bird sanctuary not far from the urban landscape of Baltimore. (To get there, though, you still have to arrange your own boat trip to the island — there is currently no commercial boat service.)

Because Maryland Sea Grant has participated in studies about how to manage the harbor’s dredged sediments, we were invited to tour the island in early June to learn about this milestone in Hart-Miller’s story and about what it takes to create and maintain an island like this.

|

|

Hart-Miller Island is officially named a “containment facility” to hold the dredged sediments. But there are few buildings or other structures located in this 1,100-acre manmade island. |

|

|

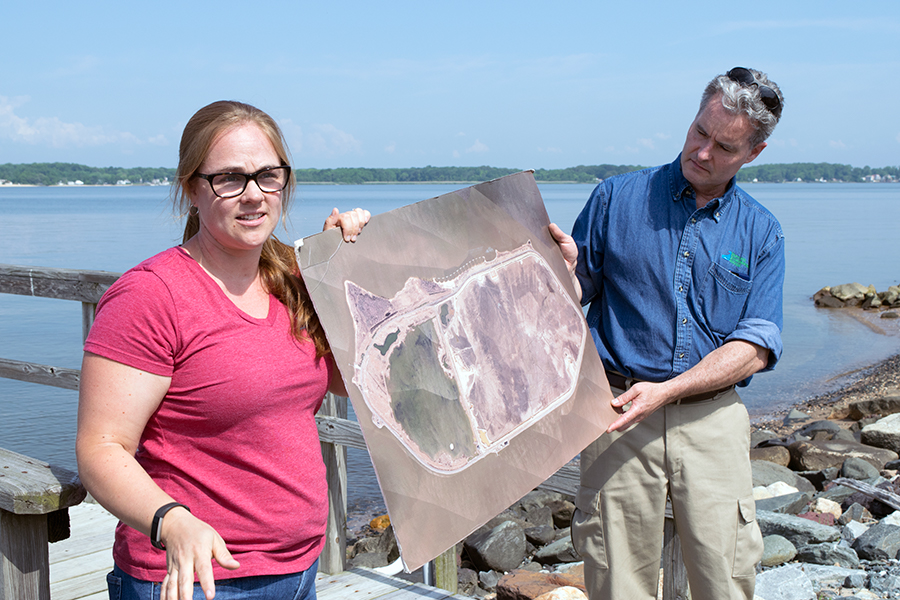

This aerial, 2011 photo of the island shows its vegetated, 300-acre south “cell” or containment area (left), which DNR is opening for public access. The 800-acre north cell is at right. The south cell was filled with sediment first (in 1990) and restoration work began there first. The south cell was filled with a pond after this photo was taken. Amanda Penafiel (left) and project manager Lincoln Tracy (right) work for the Maryland Environmental Service (MES), which conducts operations at Hart-Miller for the Maryland Port Administration. |

|

|

The north cell has attracted more than 280 species of birds. The island’s managers plan to open the north cell to public access after they plant it with vegetation as they have the south cell. Filling of dredged sediment in the north cell ceased only in 2009. |

|

|

An access road runs along Hart-Miller’s perimeter, with the Chesapeake Bay to the left. The road is built atop a dike made of sand and stone. In the south cell, the dike measures 28 feet high; in the north cell, 44 feet. |

|

|

Turning the north cell of Hart-Miller Island into park land will take more time. Work to plant native grasses, shrubs, and trees had to be delayed after two tropical storms in 2011 created a large pool of rainwater there estimated to contain 650 million gallons. When managers tested the water, they found it was too acidic to release into the Bay. The island’s operating permits prohibit managers from discharging surface water into the Chesapeake Bay unless it meets water quality standards. Because the north cell has lacked a cover of natural vegetation that can help to reduce acidity levels in rainwater, the managers left the large pool of water to evaporate, a process that lasted into 2016. To help vegetation grow in the north cell, workers will spread lime on the ground to reduce acidity levels in the dredged sediments. |

|

|

The beach on the west side of Hart-Miller Island was built outside of the dike perimeter on remnants of the original Hart and Miller Islands. On sunny weekends, the beach attracts scores of visitors who arrive on private boats. The state park also offers campsites and restrooms open May to September. The park closes at day's end, except for registered campers. The south cell will be open and staffed Thursdays through Mondays from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. |

|

|

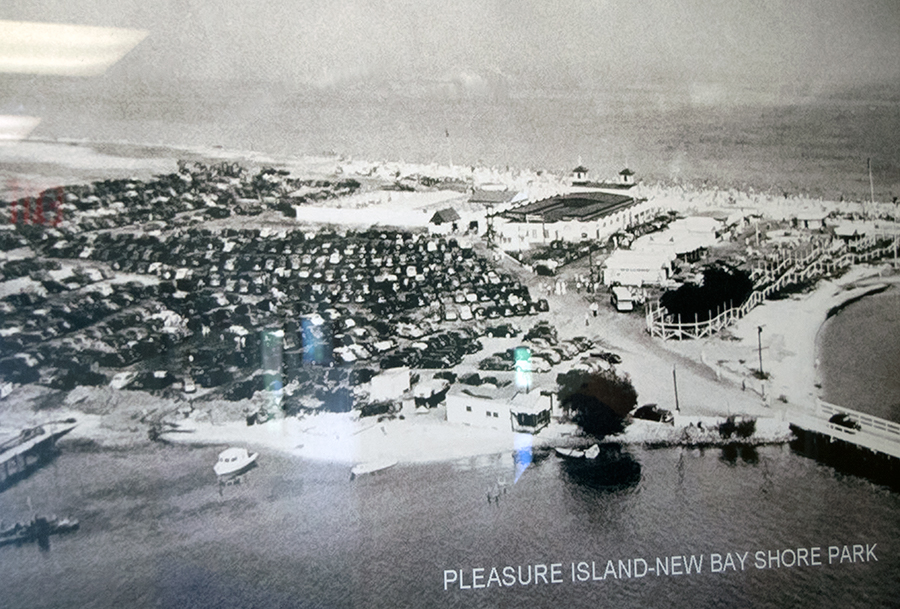

This old photo displayed in an operations building at Hart-Miller Island shows Pleasure Island, a separate island located just to the south of Hart-Miller. When Hart-Miller Island State Park was created in the late 1970s, it included the remnants of three islands: Pleasure, Hart, and Miller. Pleasure Island, which was not included in the sediment containment facility, had been privately developed in the late 1940s as New Bay Shore, which included an amusement park (right) that was accessible from the mainland via a wooden bridge. New Bay Shore was badly damaged by several storms and finally closed when the bridge washed out in the mid-1960s. Today visitors may visit Pleasure Island by boat. |

|

|

Members of Maryland Sea Grant's External Advisory Board walk out a dock on Hart-Miller Island to a Maryland Environmental Service boat that will take them back to the mainland. |

|

|

A look back at Hart-Miller Island. |

Information about visiting Hart-Miller Island State Park is available at this DNR website. Maryland Sea Grant published a report about innovative ways to reuse sediment dredged from Baltimore Harbor. Read a Chesapeake Quarterly article about Poplar Island, another manmade island and sediment containment facility that the Maryland Port Administration began operating after Hart-Miller Island reached capacity. Photos by Jeffrey Brainard except for top, right, by the Maryland Department of the Environment. |

See all posts from the On the Bay blog